The Canadian Pacific Railway was formed to physically unite Canada and Canadians from coast to coast. At CP we take great pride in our past and look to the future with the same boldness, ambition and innovation that drove the creation of the railway.

Scroll through the timelines to learn how the railway played an integral part in the building of Canada. With interesting facts and famous photos, the proud heritage of the railway is brought to life.

or

< USE ARROWS >

building the railway

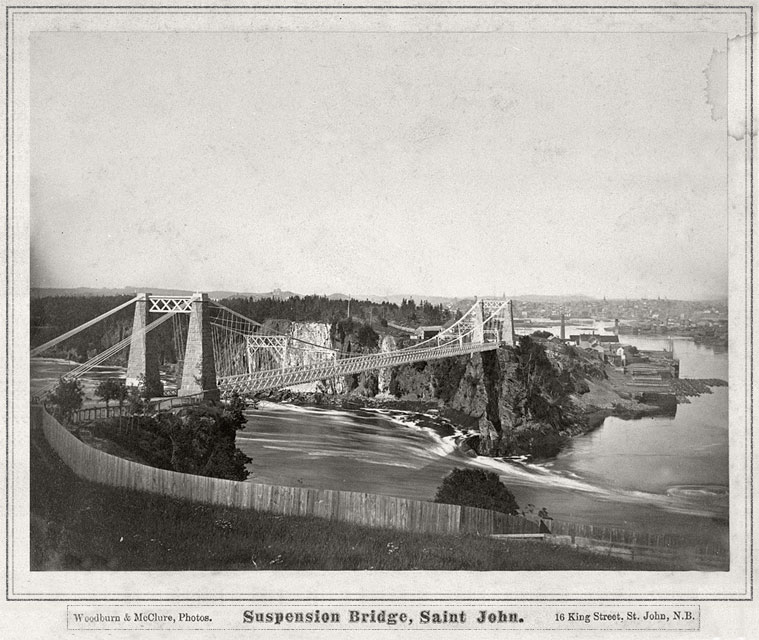

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was formed to physically unite Canada and Canadians from coast to coast. Canada’s confederation on July 1, 1867 brought four eastern provinces together to form a new country. As part of the deal, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were promised a railway to link them with the two Central Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario. In 1870 Manitoba joined confederation. On the west coast, British Columbia was enticed to join the new confederation in 1871, but only with the promise that a transcontinental railway be built within 10 years to physically link east and west.

The railway’s early construction was filled with controversy, toppling the Conservative government of John A. Macdonald in 1873 and forcing an election. By the time Macdonald was returned to power in 1878, the massive project was seriously behind schedule and in danger of stalling completely.

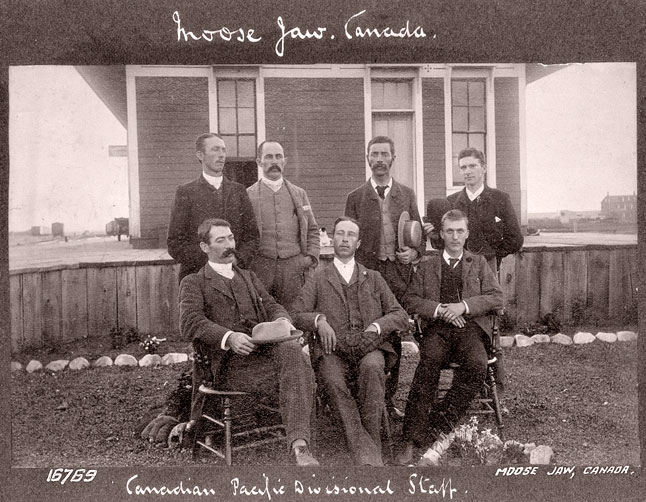

On October 21, 1880 a group of Scottish Canadian businessmen finally formed a viable syndicate to build a transcontinental railway.

The Canadian Pacific Railway Company was incorporated February 16, 1881, with George Stephen as its first President.

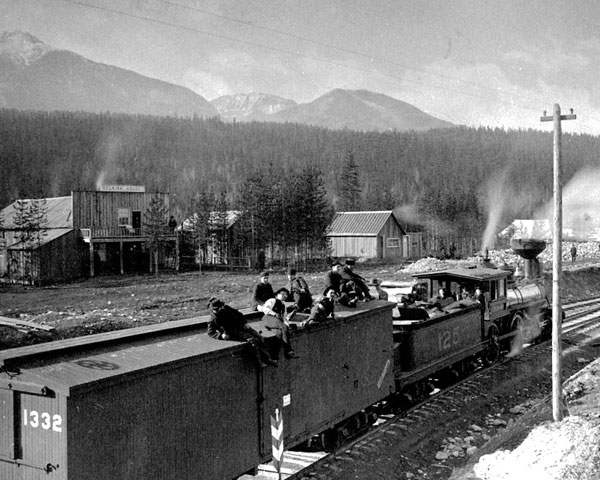

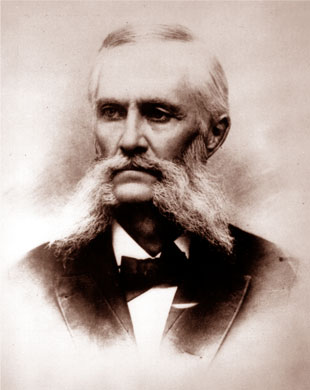

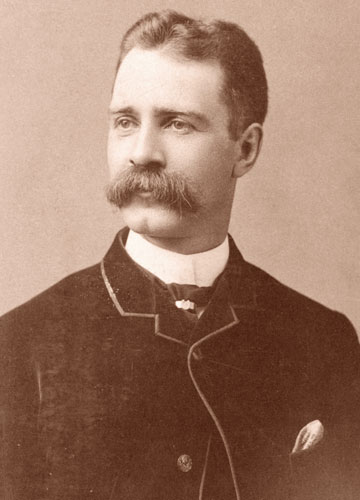

The 1881 construction season was a bust and the railway’s Chief Engineer and General Superintendent were fired at the end of the season after building only 211 km (131 miles) of track. Syndicate member and director James Jerome Hill suggested William Van Horne was the man who could get the job done. A rising star in the U.S., Van Horne was lured with a sizeable salary to become CPR General Manager and to oversee construction of the transcontinental railway over the Prairies and through the mountains.

Sir William Van Horne. Ref: NS5661

Sir William Cornelius Van Horne (1843 – 1915) is most famous for overseeing the construction of the CPR. This in itself was a great achievement, but just one of the ways Van Horne left his mark on the railway and Canada. Van Horne became one of the CPR’s first Vice Presidents in 1884. Four years later, he became the President of CPR, a job he held until his retirement in 1899. Van Horne was appointed Chairman of CPR’s Board of Directors that same year, a position he held until his resignation in 1910.

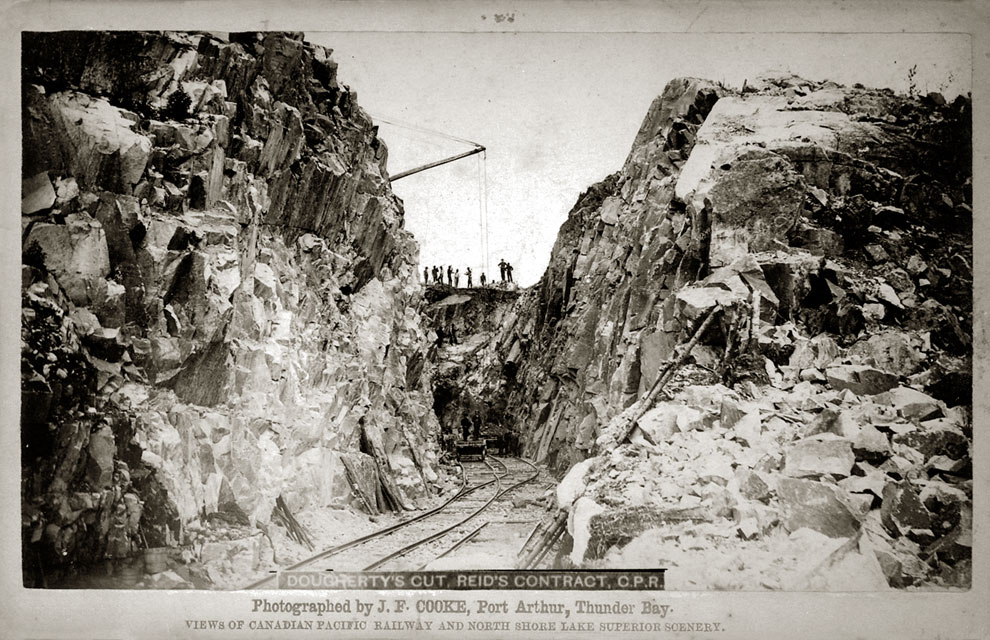

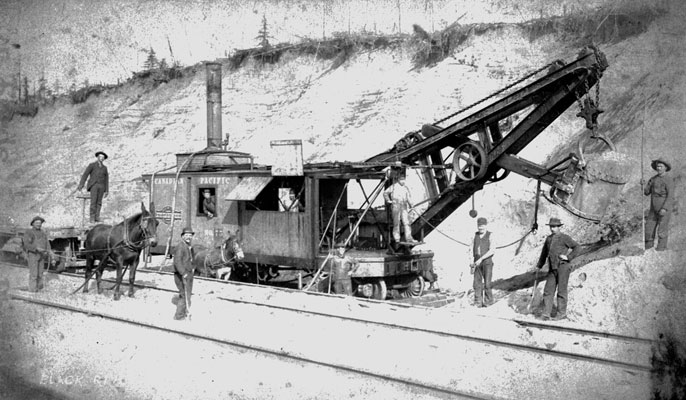

Construction by the company eventually occurred on several fronts: From the east end at North Bay, at various places on the north shore of Lake Superior supplied by boat, and from Winnipeg westward. Government construction continued from Port Moody to Kamloops Lake, and from Winnipeg to Lake Superior (present Thunder Bay).

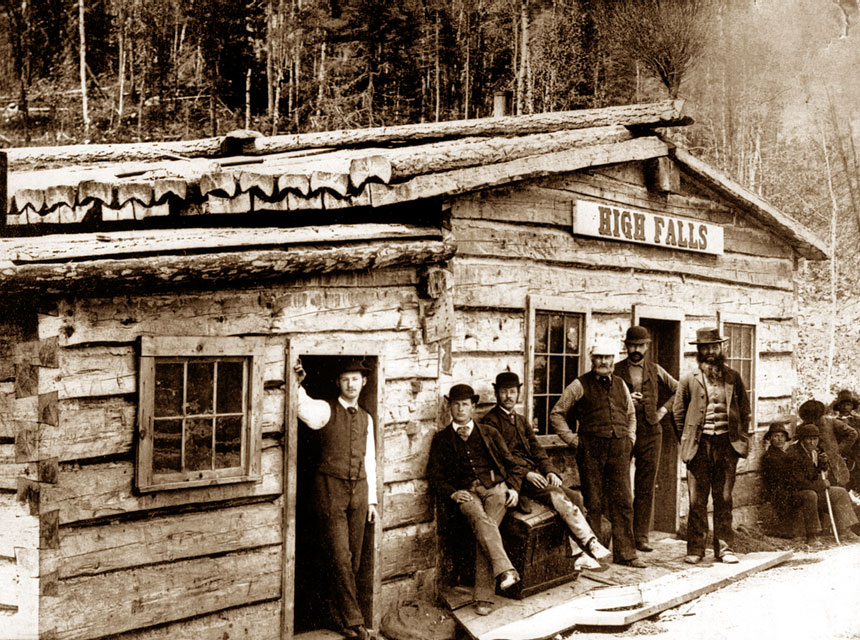

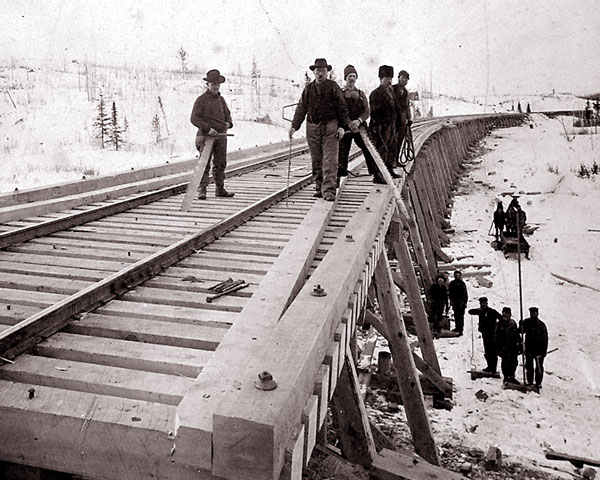

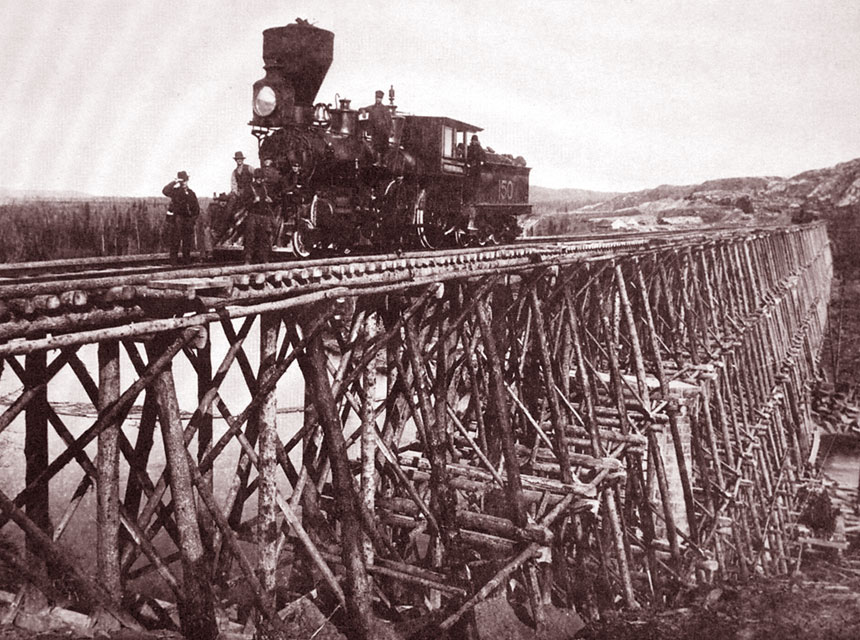

Near Kenora, ON, 1881-82. Ref: NS2365

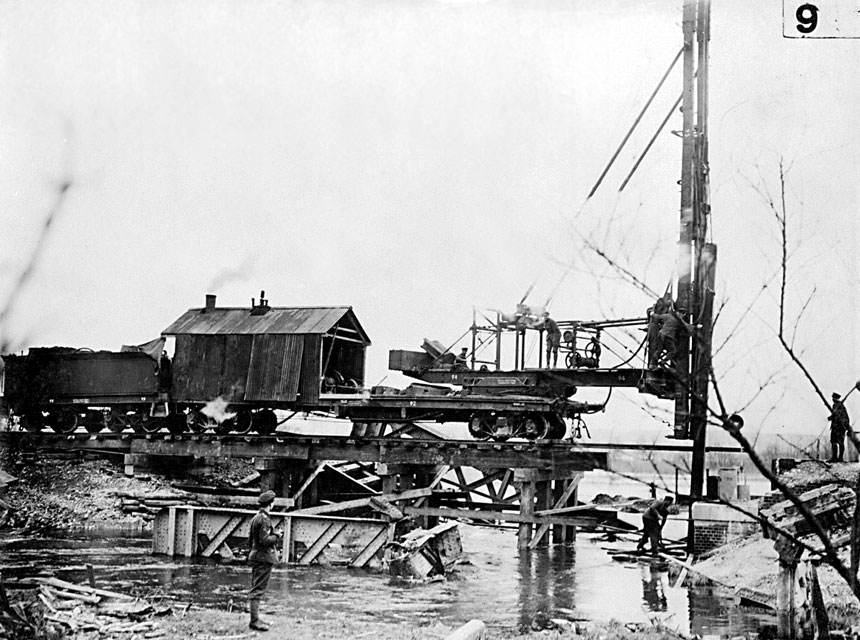

A crew completes the work on a trestle near Rat Portage (near Kenora, ON) in the winter of 1881-82. At that time, the Government of Canada was responsible for construction of the transcontinental railway on the difficult terrain from the lake-head to Winnipeg, MB.

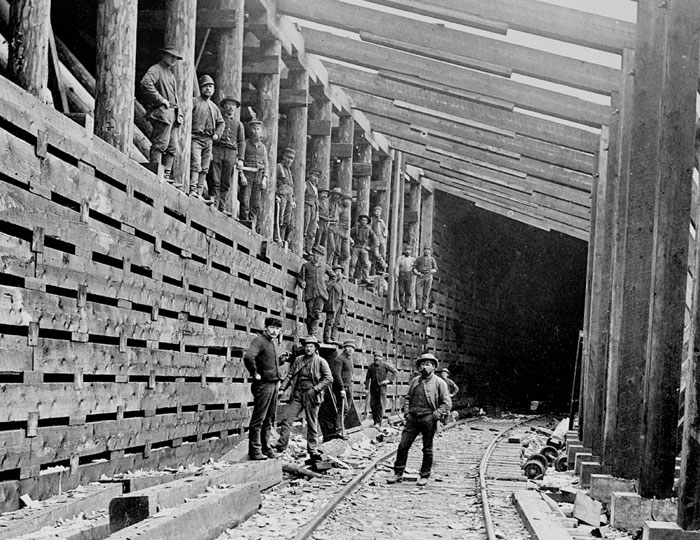

Heron Bay, ON, 1885. Ref: NS14886

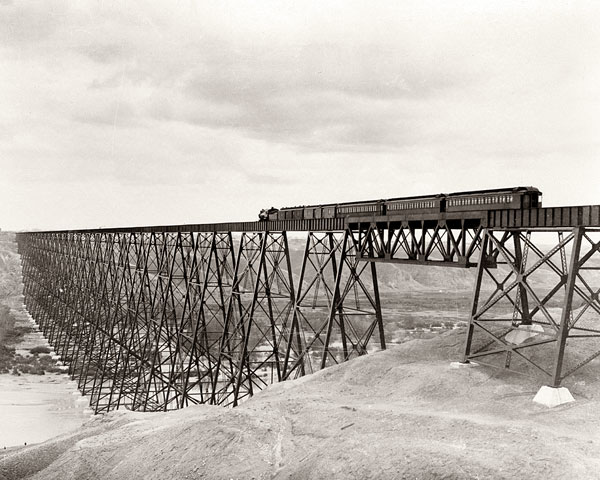

An eighty foot-high and six hundred foot-long temporary pole timber trestle spanning the Pic River, east of Heron Bay in northern Ontario, in 1885. The Laurentian Shield has many major river crossings, and rather than wait for each bridge to be designed and built out of steel, temporary bridges such as this one were used. This allowed the railway to continue moving supplies and men forward for the track construction.

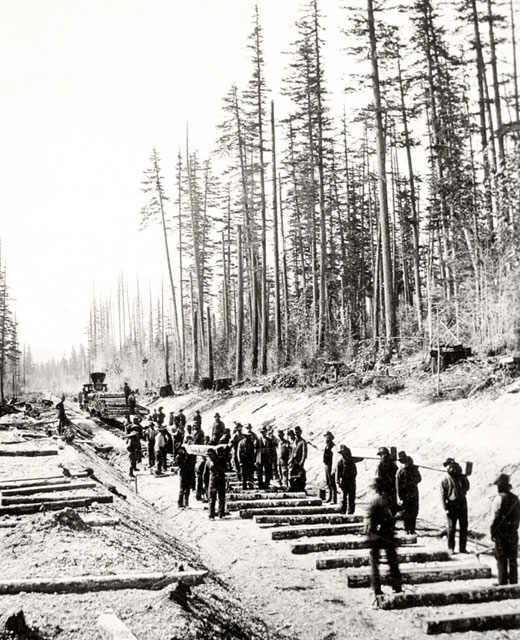

Given that the Prairies are relatively flat with no granite or hard rock to blast through, records were broken frequently during construction for the number of miles per day completed.

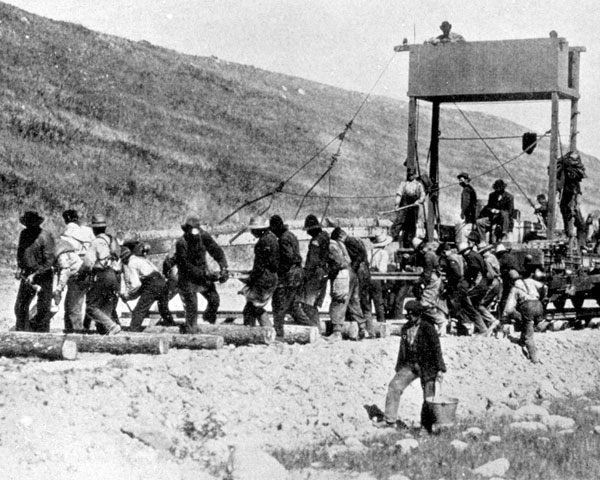

With long summer days, dry conditions, and an experienced tracklaying crew, up to five miles of track were laid per day. The amount of material and manpower required to build a mile of track was not insignificant — 2,800 railway ties were required for each mile of track, all carried on shoulders from flatcars to waiting wagons for transport to the front of the work line. Many of the workers in the tracklaying crew were immigrants from Europe, and often up to 200 men would be working together to move the track forward.

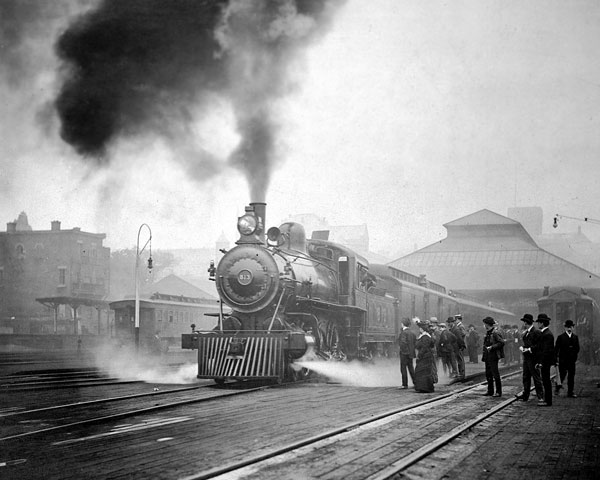

Winnipeg, MB, 1877. Ref: NS17756

The first railway rolling stock to appear on the Canadian Prairies arrived in Winnipeg on October 9th, 1877 after being barged 226 miles down the Red River from Fargo, North Dakota. Purchased by Joseph Whitehead, the government contractor responsible for building the CPR line between Emerson and St. Boniface, the shipment included “CPR” locomotive No.1, soon to be christened the “Countess of Dufferin”.

Gull Lake, SK, circa 1890's. Ref: NS17161

For centuries, the First Nations people of the Plains hunted the plentiful herds of buffalo as a source of food, shelter and clothing. With the completion of the railway and the dramatic increase in the numbers of settlers, the buffalo was hunted almost to the point of extinction. For a time in the late 19th century, First Nations people and Métis collected buffalo bones at locations such as Gull Lake, SK, selling them by the ton for shipment to the manufacturing centres in the east where they were converted into phosphate for fertilizers.

The best way to show that the railway was coming to British Columbia was to start building tracks. In 1879, the Canadian government hired an American contractor, Andrew Onderdonk, to start construction. Over the next seven years 15,000 men, including many Chinese labourers, built 545 km of track from Port Moody to Craigellachie in Eagle Pass, where he ran out of rail.

The work was dangerous and cut through some of the most treacherous geography in the Fraser Canyon. Many workers lost their lives building this section of the transcontinental railway, but the tracks built by these men showed British Columbians the railway was on its way. Canada had kept its promise — British Columbia decided to remain part of the country.

Andrew Onderdonk, circa 1880.

Andrew Onderdonk (1848 – 1905) was an American engineer and construction contractor who worked on several major projects in the West, including the San Francisco seawall and the CPR.

After his work for the CPR, Onderdonk won additional contracts for railway and canal construction in the U.S. and eastern Canada. In 1895 he received a contract from the Canadian government to build sections of the Trent-Severn Waterway in Ontario.

Image courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives, Major Mathews collection, Item # Port P587.02

On May 27, 2005, Canadian Pacific Railway named the railway interchange in Kamloops, British Columbia after Chinese labourer Cheng Ging Butt. The Cheng Interchange honors the many labourers who toiled, some sacrificing their lives, to build the western section of the CPR from Port Moody to Craigellachie, BC. For many years, the contribution of the Chinese railway workers went largely uncelebrated.

Fifteen years ago CPR, working with the Chinese community, erected a monument in Toronto honouring Chinese railway labourers. More recently, the Royal Canadian Mint launched a two-coin commemorative set marking the 120th anniversary of the completion of the CPR and the important part played by the Chinese workers in building the railway. In 2005, CPR, once again building track to expand in the West, took the opportunity to celebrate the Chinese workers from the 1880s with the dedication of the Cheng Interchange.

In 1882, with Van Horne in charge of construction, crews laid 673 kilometers of track. By the end of 1883, the railway had reached the Rocky Mountains, just eight kilometres (five miles) east of Kicking Horse Pass.

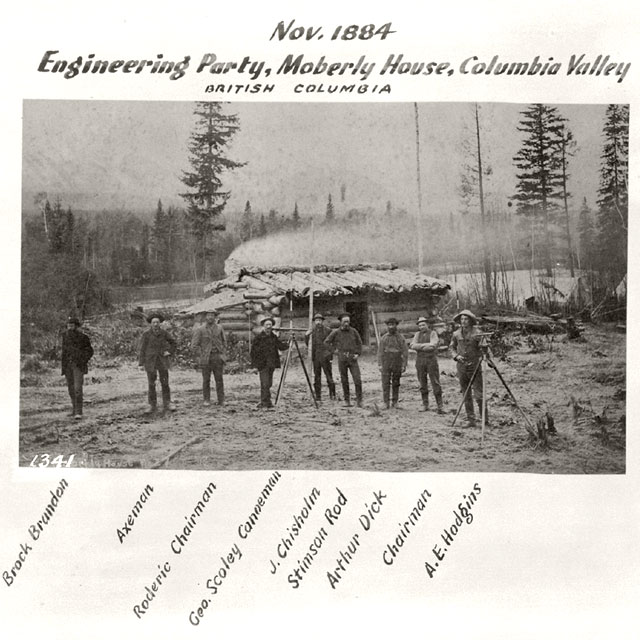

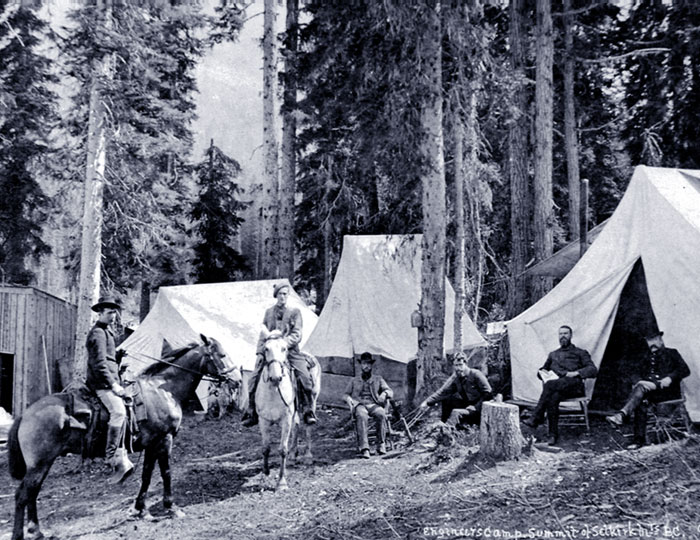

The construction seasons of 1884 and 1885 would be spent in the mountains of British Columbia. With no modern materials or machinery, building the railway through the Rocky and Selkirk Mountains was a formidable task.

During the 1870s when the CPR was being planned, the preferred route through the Rocky Mountains was the northerly Yellowhead Pass (near Jasper). When the railway construction project was turned over to a private company in 1881, the route was changed to the Kicking Horse Pass (west of Lake Louise). While the railway was being built across the prairies, the railway company had to find a pass over the unexplored Selkirk Mountains, or else it would have to detour around them which would add considerable cost as well as travel time. Major A. B. Rogers was hired in April 1881 by the railway company to find the pass. It took him two years to find a pass that the railway could use – which was named Rogers Pass in his honour. He also received a cheque for $5,000 and a gold watch.

Rogers Pass is known for its winter snowfall, which amounts to about 10 metres per year. Because of steep mountains, avalanches are very common in winter. 31 snow sheds with a total length of about 6.5 km were built to protect the railway from the avalanches.

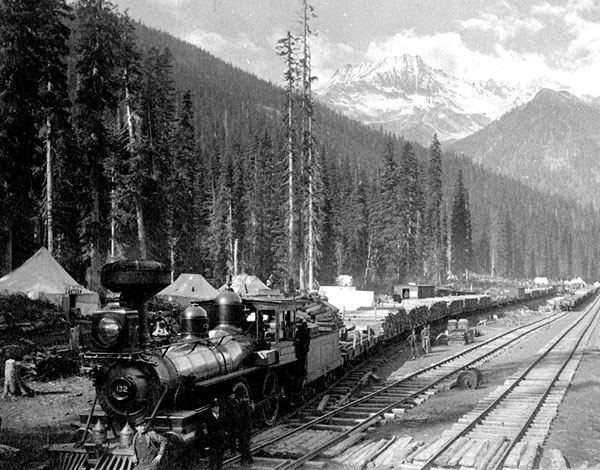

Field, BC, circa 1886. Ref: A18885

Located on the CPR main line at the western entrance of Rogers Pass, the Glacier House was the most popular of the three small mountain hotels established by the company in 1886 at Field, Glacier and North Bend, BC, to provide meals for train passengers and lodging for those wishing to stop over and admire the scenery.

On Nov. 7, 1885, the eastern and western portions of the CPR met at Craigellachie, B.C., where Donald A. Smith drove the last spike.

The cost of construction almost broke the syndicate, but within three years of the first transcontinental train leaving Montreal and Toronto for Port Moody on June 28, 1886, the railway’s financial house was once again in order and CPR began paying dividends again.

Craigellachie, BC, 1885. Ref: NS1960

On November 7, 1885, a group of Canadian Pacific officials and employees gathered in Eagle Pass in British Columbia to witness one of the most significant events in Canadian history. At 9:22 a.m. Pacific Time, Donald A. Smith, a member of the CPR syndicate and later Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, drove the last of the iron spikes in the Canadian Pacific Railway main line linking Eastern Canada and the Pacific Coast. Notable figures present on this historic day included: Frank Brothers, Construction Foreman; W.C. Van Horne, Vice-President; Sandford Fleming, Director; Henry J. Cambie, Supervising Engineer; James Ross, Manager of Construction and Major Rogers, Engineer.

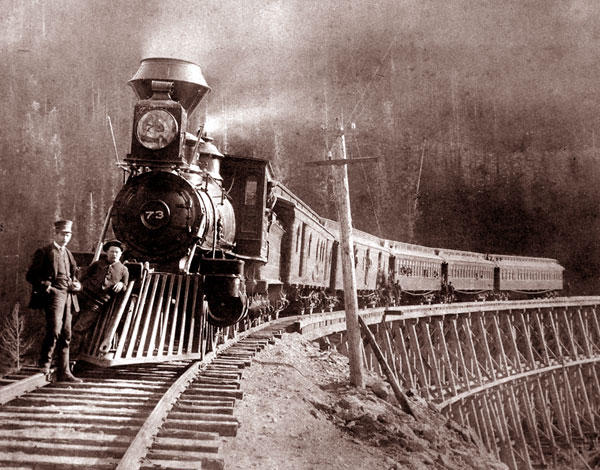

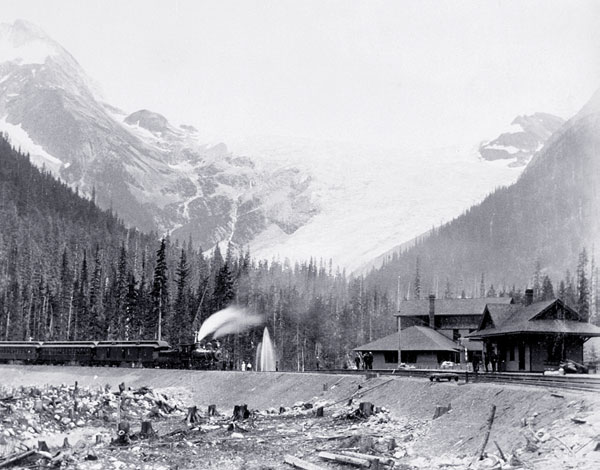

Port Moody, BC, 1886. Ref: NS19991

At noon on July 4th, 1886, the first scheduled passenger train to cross Canada over the CPR’s recently completed line arrived “sharp on time” at Port Moody, BC, the company’s western–most terminus. The momentous journey began 139 hours earlier with the departure of the westbound “Pacific Express” from Montreal.

In 1886, the CPR had constructed a few small hotels to accommodate travellers, with the goal being to primarily provide meal service for passengers in the Rocky Mountains, where railway grades were too severe for the safe operation of heavy dining cars. They were also natural stopover points for weary travellers who needed a hotel room for the night on their travels.

tourism & recreation

near Rogers Pass, BC, 1887. Ref: A11357

Located on the Canadian Pacific Railway main line at the western entrance of Rogers Pass, the Glacier House was the most popular of the three small mountain hotels established by the Company in 1886 at Field, Glacier and North Bend, BC to provide meals for train passengers and lodging for those wishing to stop over and admire the scenery. Situated near the foot of the Illecillewaet Glacier, the hotel became a favourite stopping place for tourists and climbers eager to explore the glacier and challenge the surrounding peaks.

Glacier House, BC. Ref: A8183

Nestled near the foot of the great Illecillewaet Glacier and surrounded by the peaks of the Selkirk Range, the CPR’s Glacier House hotel opened for business shortly after the completion of the transcontinental railway through the area in 1886. The hotel soon grew to become the headquarters for mountain climbing within the new Glacier National Park and the first recorded mountaineering expedition in Canada set out from here in 1888. Pictured here at the height of its popularity in the early 1900s, the hotel had expanded from six to ninety guest rooms, and even boasted of having a billiard parlor and a bowling alley. Unfortunately for the hotel, the relocation of the railway through the Connaught Tunnel in 1916, the growing success of the Company’s hotels at Banff and Lake Louise, and the gradual retreat of the Great Glacier resulted in a steady decline in patronage and the Glacier House was closed down at the end of the 1925 season.

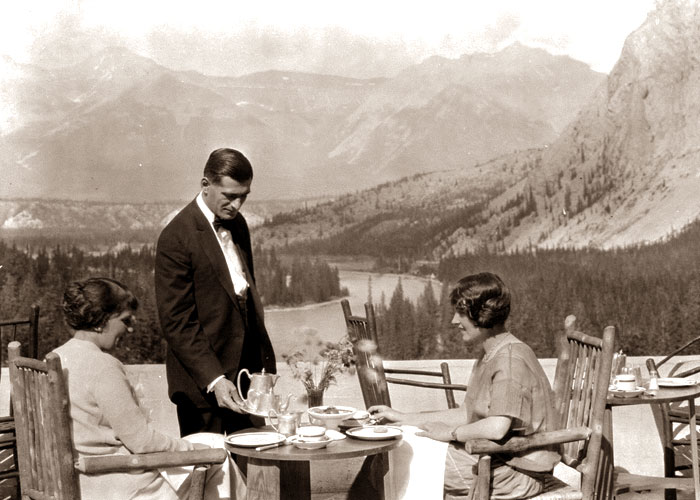

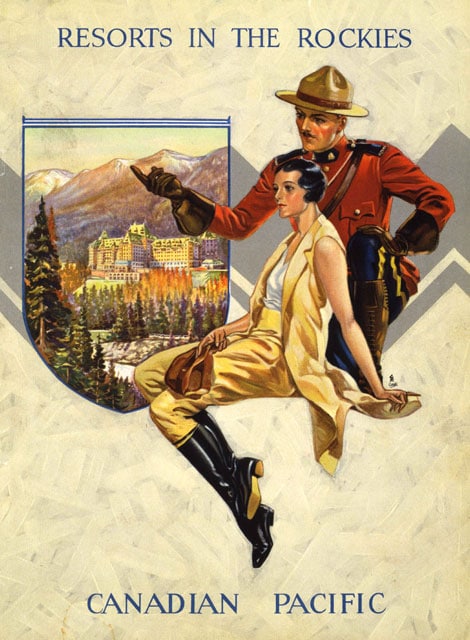

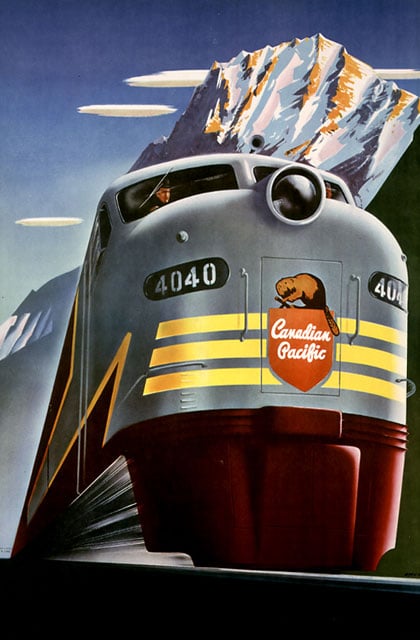

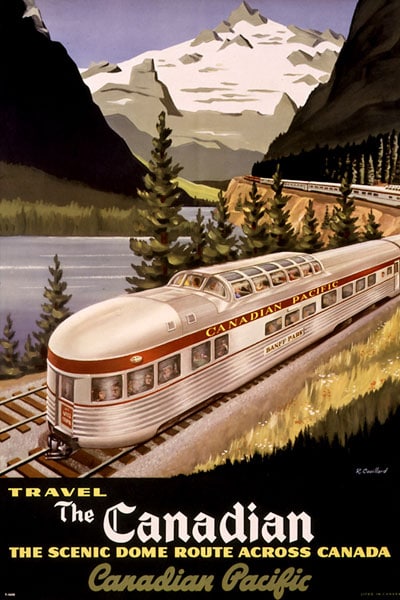

CPR president William Van Horne envisioned a string of grand hotels across Canada that would draw wealthy visitors from abroad to his railway. The CPR began to advertise the scenic mountain ranges and vistas that its network spanned as places to visit and it built company owned luxury hotels at these destinations for travelers.

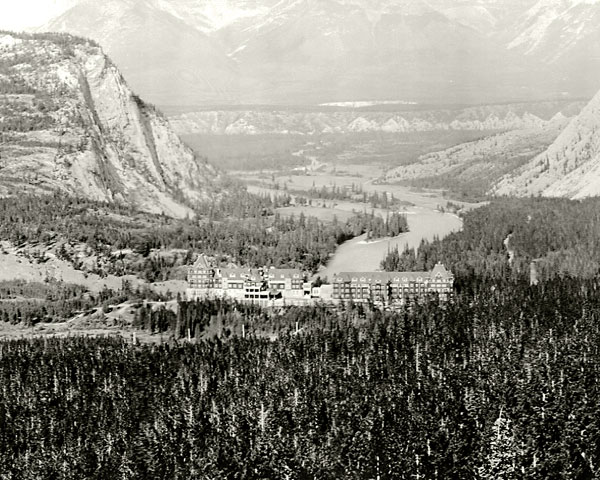

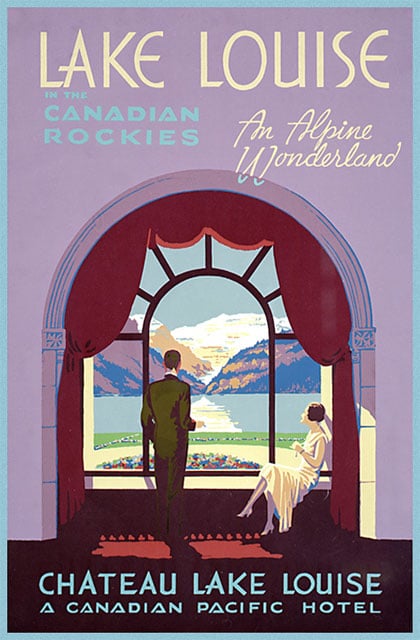

The Banff Springs Hotel opened in 1888, on a site that was personally chosen by Van Horne. It quickly became a popular tourist destination for the rich, with magnificent vistas and quick access to the relatively unexplored mountains and lakes of the Rockies. Chateau Lake Louise opened in 1890 to similar acclaim. The CPR also operated a number of small hotels and bungalows in remote areas to offer guests additional recreational opportunities in the wilderness.

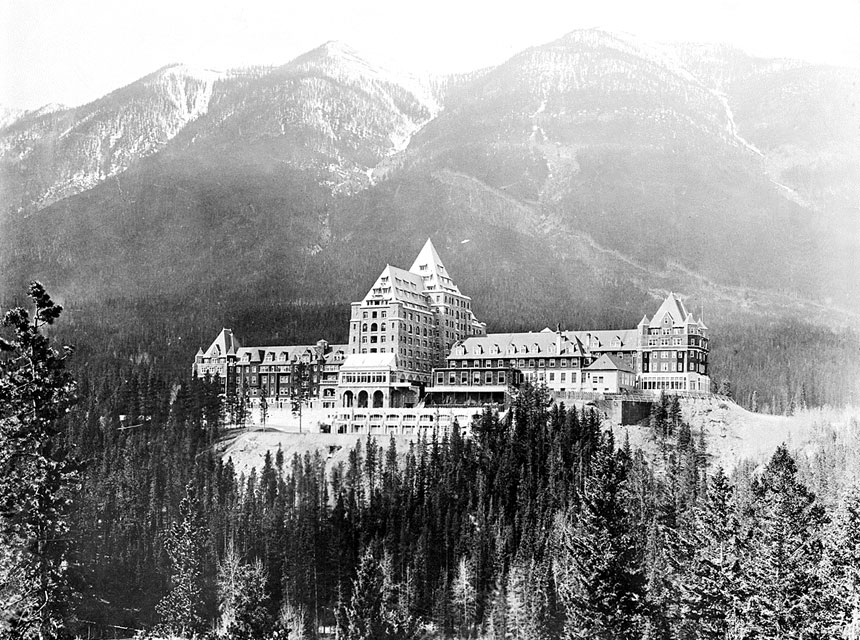

Banff, AB, circa 1911. Ref: A32207

A view of the Banff Springs Hotel from the slopes of Sulphur Mountain. The building was designed by American architect Bruce Price and was built in the Scottish Baronial style between the spring of 1887 and the spring of 1888. Additions to the Banff Springs Hotel were completed in 1902, 1911, 1914, 1926 and 1928, necessitated by the growing volume of tourist traffic.

The hotel is located within a spectacular setting in the Rocky Mountains, just above the Bow Falls and close to thermal hot springs. The main view from the hotel is across the valley and toward Mount Rundle.

The 1888 structure cost $250,000 and a mistake made by the builder changed the intended orientation of the building, turning its back on the mountain vista.

Banff, AB, 1929. Ref: A32210

By 1906, plans were advanced for a complete overhaul of the Banff Springs Hotel, with much of the original structure being replaced. Walter Painter, chief architect for the CPR at the time, designed an eleven-storey central tower in concrete and stone, flanked by two wings. He corrected the mistake of the original structure, and oriented the building to take advantage of the dramatic view. The so-called “Painter Tower” was completed in 1914 at a cost of $2 million with 300 guest rooms and, for some time, became the tallest building in Canada. Construction of the new wings was delayed by World War I.

Further renovations were designed by architect, J. W. Orrock, who continued in the style originated by Painter, greatly expanded the Painter Tower, altering its roof line, and adding his own massive additions. In 1926, while work was proceeding on the new wings, a fire destroyed the remainder of the original building designed by Price. The two new wings opened in 1928.

In 1883, three CPR employees came across hot springs on Sulphur Mountain, near modern day Banff. Two years later, in response to competing claims of ownership over the springs, and at the urging of the CPR, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald decided to set aside a small reserve of 26 km2 around the hot springs at Cave and Basin as a public park known as the Banff Hot Springs Reserve in 1885.

The Canadian government and the CPR then began working to develop the springs as a tourist destination to increase traffic on the CPR and ensure the profitability of the railway.

Under the Rocky Mountains Park Act, enacted on 23 June 1887, the park was expanded to 674 km2 and named Rocky Mountains Park. This was Canada’s first national park.

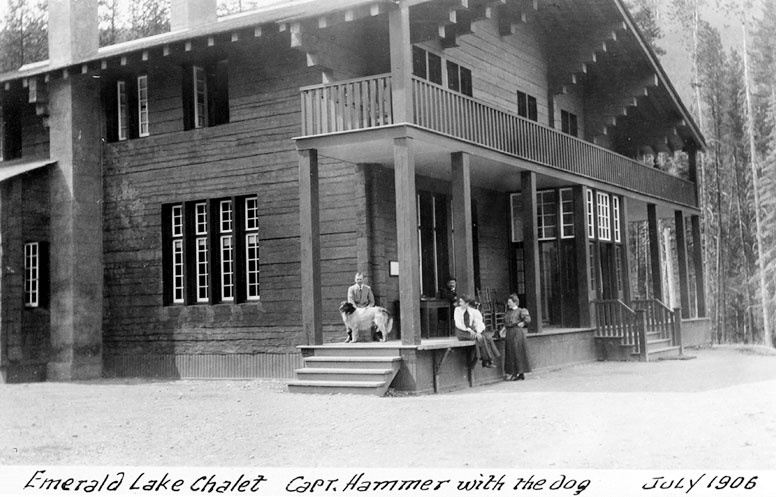

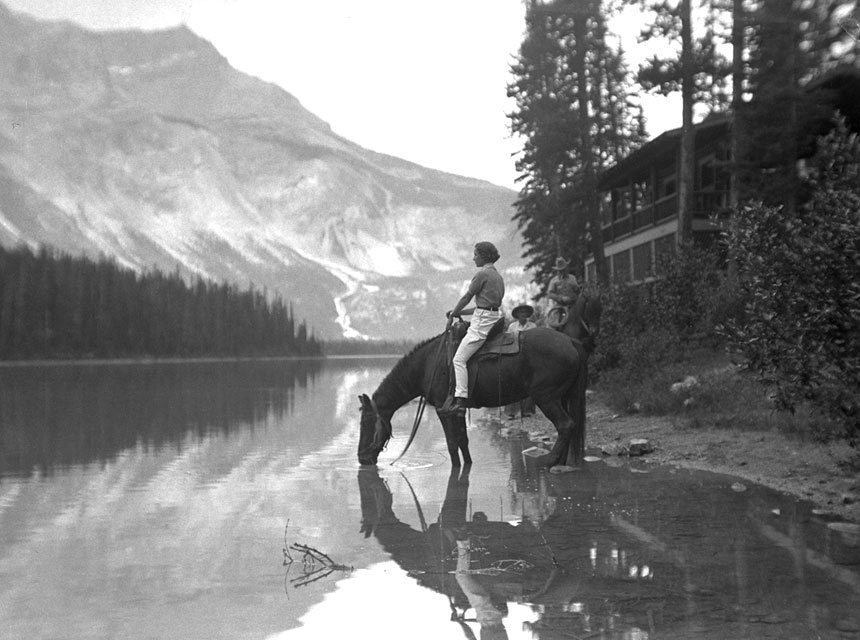

Emerald Lake, BC, 1906. Ref: NS7858

The first non-indigenous person to see Emerald Lake was Canadian guide Tom Wilson, who stumbled upon it by accident in 1882 while working with a surveying party for the CPR. A string of his horses had gotten away, and it was while tracking them that he first entered the valley. He named the lake “Emerald Lake” due to the vivid turquoise color of the water, which is caused by powdered limestone in the water.

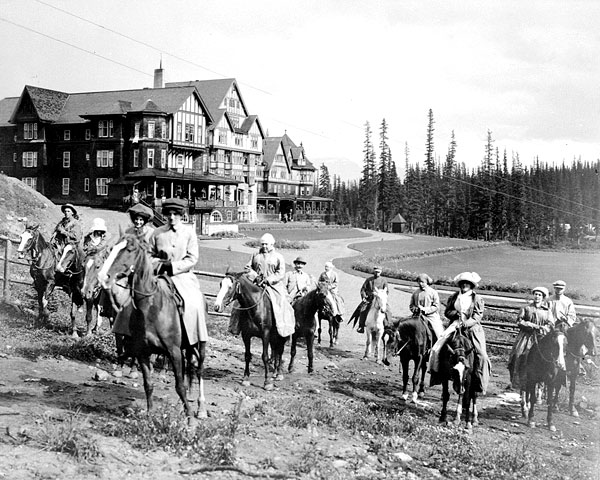

Lake Louise, AB, 1914. Ref: NS1498

A party of guests sets out from the Chateau Lake Louise for a horseback tour of the neighboring trails.

The Chateau Lake Louise, opened in 1890 as a single-storey building of log construction. Subsequent additions were made to it in 1893, 1900, 1906, 1911, 1913, 1924 and reconstruction in 1925.

Between 1890 and 1950 the CPR continued to expand its luxury hotels across the country. They built two types of hotels: urban and rural resort. The urban hotels were located near a city’s major passenger station and were intended for use by elite passengers of CPR trains.

These hotels served businesspeople and visitors, as well as passengers requiring overnight accommodation between connecting trains. The rural resort hotels were located in areas served by the CPR which had unique scenery, allowing these properties to be marketed as tourist destinations for passenger train travellers.

Although all were architecturally different, an emphasis on granite stonework and copper roofs were common elements, and many were designed to look similar to European castles.

Vancouver, BC, circa 1890. Ref: A11535

The first Canadian Pacific hotel at Vancouver was situated on the southwest corner of Granville and Georgia streets, overlooking a swampy plot of ground which eventually became the “CPR Park”, complete with lawns, tennis courts and a bandstand. Designed by Thomas Sorby, the architect responsible for the Company’s early mountain hotels at Glacier, Field and North Bend, BC, the Vancouver Hotel was officially opened in the spring of 1888 and in spite of its rather homely outward appearance soon became a source of pride for the fledgling west coast city. Positioned at the junction of Canadian Pacific’s transcontinental railway and trans-Pacific steamship services, the hotel prospered. In 1893 the first of several additions began transforming the original structure into an elegant 600-bedroom hotel which was completed in 1917 and rated by the press as “one of the finest on the North American continent”.

Quebec City, QC, 1901. Ref: A4989

Chateau Frontenac in Quebec City as it appeared at the turn of the century. Opened in 1893, the hotel remains the most distinctive and familiar feature of the Quebec City skyline and fronted by Dufferin Terrace, a popular promenade for tourists, overlooks the St. Lawrence River and the narrow, winding streets of the old Lower Town, which dates back to the founding of the city by Samuel de Champlain in the early 1600s.

Montreal, QC, 1902. Ref: A12737

CPR’s Place Viger Hotel in Montreal was erected in 1898, one block north of the Company’s former Dalhousie Square passenger terminal from which the first CPR transcontinental train had departed for the Pacific coast 12 years earlier. The ground floor of the new hotel doubled as a terminal for CPR trains bound for Quebec City and the Laurentian Mountains vacation areas north of Montreal. After many successful years, the popularity of the hotel began to wane as the city’s business district drifted westward. In 1935 the building was closed as a hotel, although for a brief period following the Second World War it served as temporary accommodation for British war brides of Canadian servicemen. Place Viger station remained in use until 1951 when the building was sold to the City of Montreal and converted into an annex for city hall.

Sicamous, BC, circa 1925. Ref: A8195

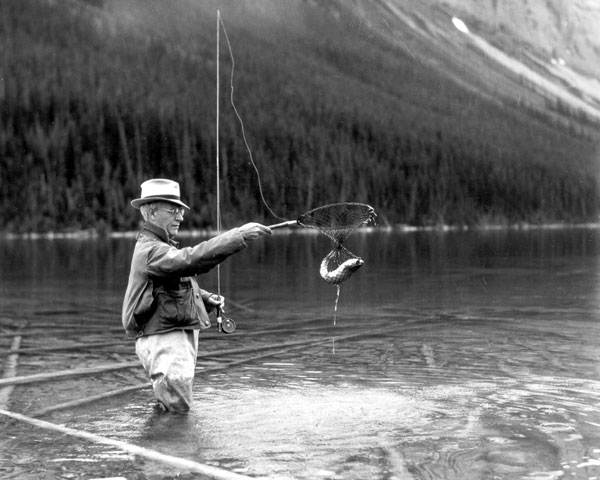

Canadian Pacific’s Hotel Sicamous was located on scenic Shuswap Lake in British Columbia, 45 miles west of Revelstoke, at the junction of the Company’s transcontinental main line and a branch line extending south to the Vernon area and the CPR steamboat service through the Okanagan Valley. Erected in 1898 on a narrow strip of land between the tracks and the lakeshore, the building served as both a hotel and railway station and catered not only to transient guests awaiting train connections but also vacationers and fishermen, for whom the CPR provided rowboats, motor launches and even a houseboat. In 1910 the hotel was enlarged by the addition of a third storey, doubling the number of guest rooms. Hotel Sicamous was to remain in operation until 1956 and the station, which occupied part of the main floor, survived for another eight years before being closed and the building demolished shortly afterwards.

Toronto, ON, 1928. Ref: A8861

The Royal York Hotel, which opened on June 11th 1929, was once billed as the largest hotel in the British Empire and one of the finest on the continent.

The steel skeleton has been completed and the limestone outer walls are progressing upward in this view of the Royal York Hotel in Toronto under construction.

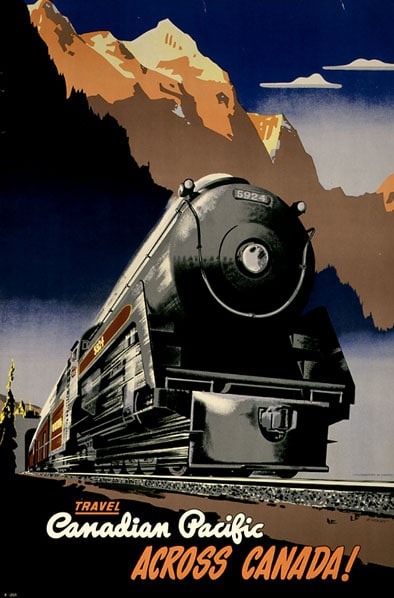

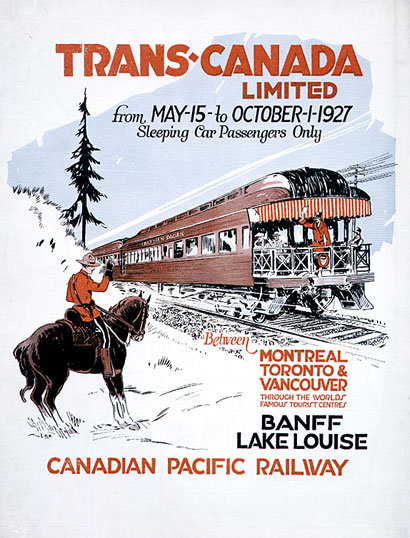

Prior to the opening of the CPR, getting from one end of Canada to the other was nearly impossible, and would have taken months via boats, horseback and on foot. Once open, a trip across the country could be counted in days.

As wealthy business people, high ranking government officials and rich travellers crossed Canada via the newly built CPR — many en route to Asia, word quickly spread about the stunning, unspoiled scenery.

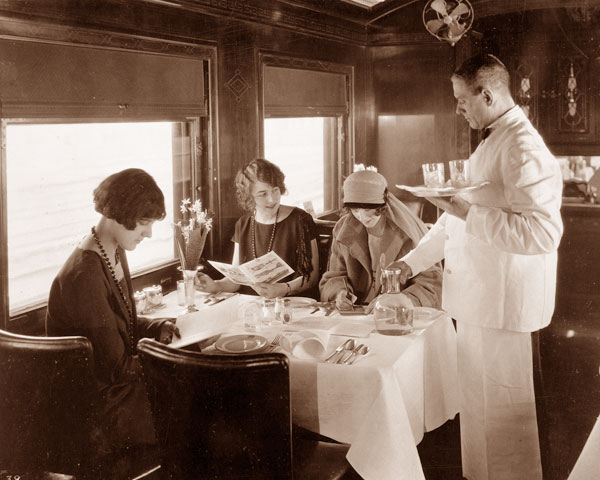

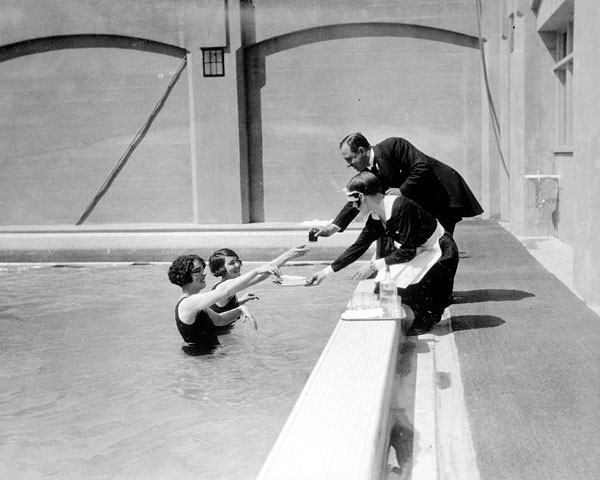

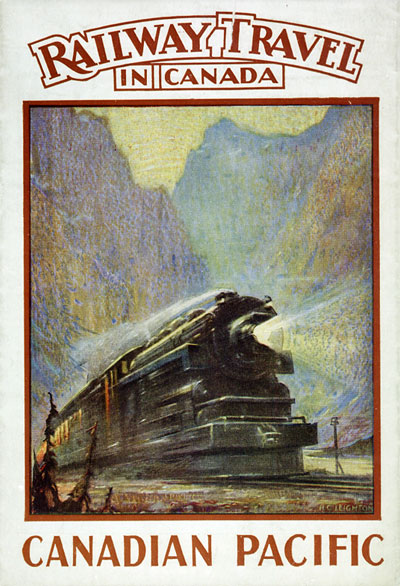

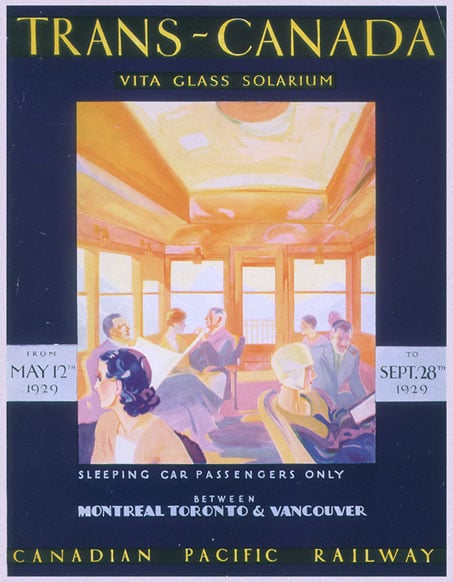

CPR capitalized on this opportunity not only with its hotels, but also by offering luxurious services on its trains.

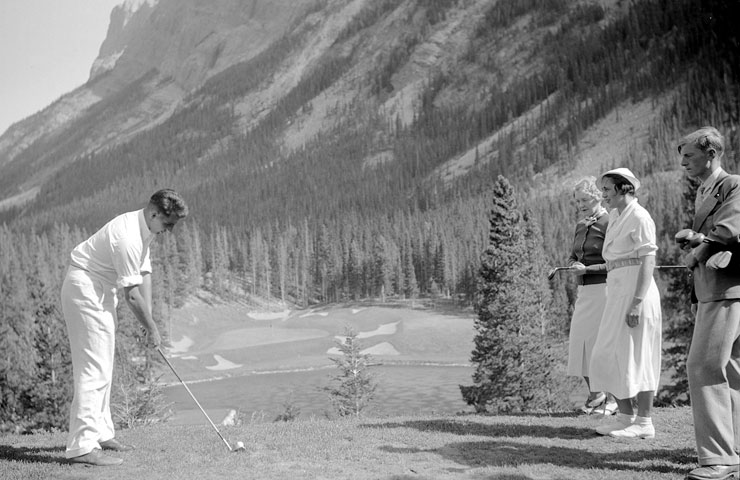

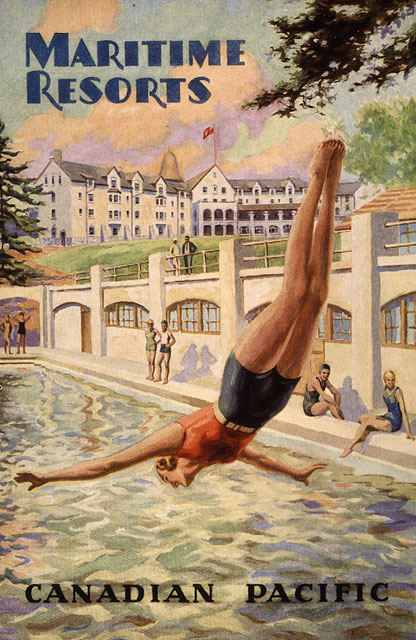

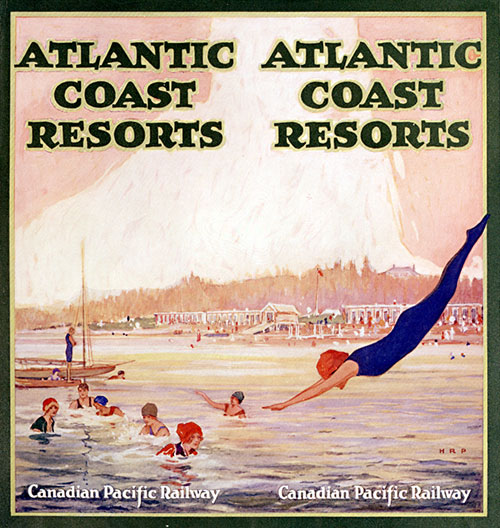

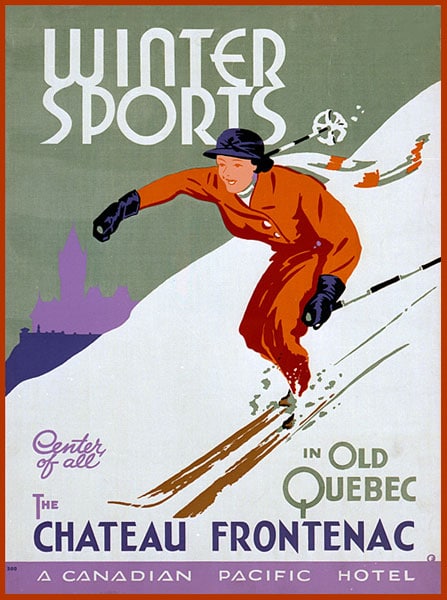

The CPR resort hotels offered a wide assortment of activities for guests. Swimming, sailing, golfing, hunting, fishing, canoeing and trail riding were popular activies in the summer, and in winter skating, toboganning and skiing were promoted.

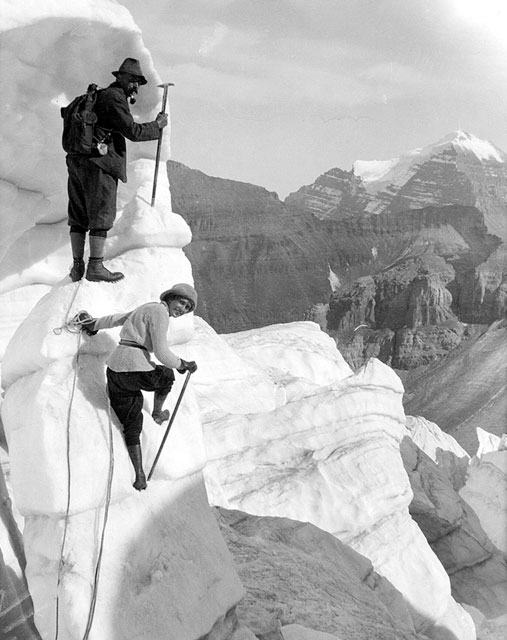

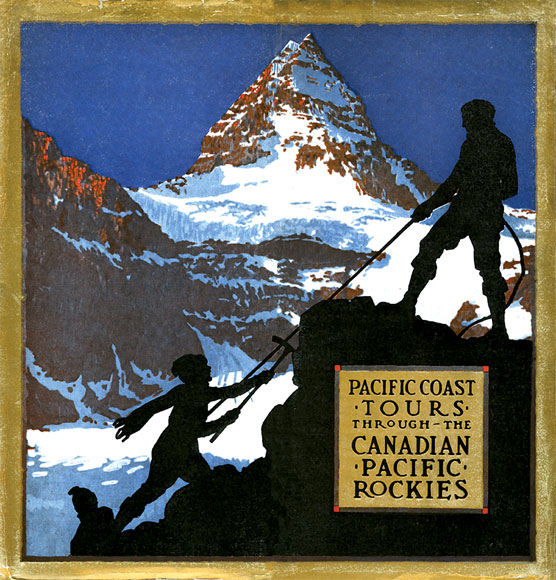

In the 1890’s the CPR heavily marketed the Rockies as an unexplored “Canadian Alps.” Professional Swiss mountaineering guides were hired in 1899 to ensure the safety of the clientele and to complete the marketing picture of the Rockies as the Alps. Most of their time was spent in Glacier (near Rogers Pass), Field and the Lake Louise area, but they also explored and led expeditions to Jasper and beyond.

The Swiss guides amassed a record of over 170 first ascents in the Rocky Mountains, with not a single fatality between 1899 and 1955.

Moraine Lake, AB, 1926. Ref: NS85

Accomplished mountain climber Georgia Englehard’s first climb in 1926 to Pinnacle Peak above Moraine Lake with CPR guide Edward Feuz. In the 1931 season alone, Ms. Englehard made 38 ascents, mostly in the Yoho area and the Selkirks. Throughout her career she climbed Mt. Victoria 13 times.

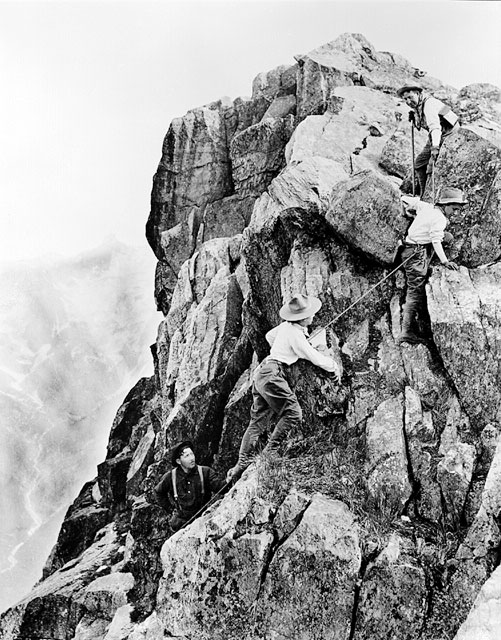

near Lake Louise, AB, 1910. Ref: A10976

A party of climbers ascends Mount Abbott under the watchful eyes of their Canadian Pacific Swiss Guides. The Company encouraged the growth of mountaineering as both an adventurous and scientific pursuit by introducing the guides in 1899, and providing shelters for climbers in remote areas of the Rockies and Selkirks. Hermit Hut, overlooking Rogers Pass in the Selkirks, was the first such facility to be erected in Canada.

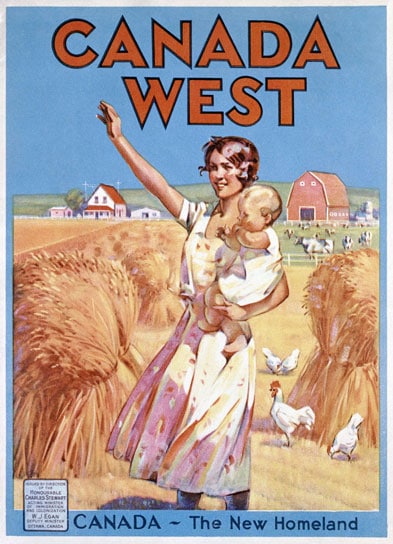

The CPR played a crucial role in the settlement and population of western Canada. In order for the railway to be profitable, it needed passengers and cargo, but the west was very sparsely populated when the railway was first built.

CPR management realized this was an issue, and as early as 1881, the railway became actively involved in land settlement and land sales.

The CPR actively recruited immigrants and settlers to come west by selling them farm land from the railway’s original 25 million acre land grant at bargain prices.

immigration & settlements

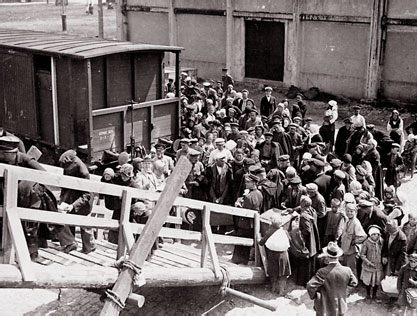

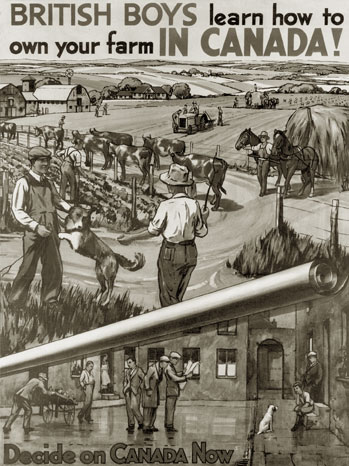

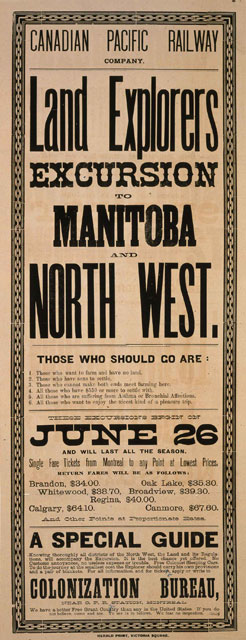

The CPR didn’t just advertise for settlers in eastern Canada, it also ran advertisements in European newspapers to tell people about the fertile farmland of the Canadian Prairies. In 1909, CPR spent more money promoting immigration than the Canadian government.

Agreements were struck with various European governments to aid in the immigration process.

Liverpool, Great Britain, 1923. Ref: A12293

The first contingent of British harvesters bound for the Canadian Prairies during the 1923 season awaits departure from Liverpool aboard the CPR steamer Montclare. The annual harvest excursions drew tens of thousands of men from Great Britain and Europe, to assist in the harvesting of the crops, many of whom remained as settlers.

Regina, SK, circa 1920s. Ref: NS22147

In the early 1920s a group of women immigrating to Canada pose on the steps of the Regina Women’s Hostel. The CPR pamphlet — Openings for British Women in Canada — available through the company’s head office in London, described a wide range of employment opportunities available and the conditions women could expect to encounter.

Montreal, QC, circa 1920s. Ref: NS13729

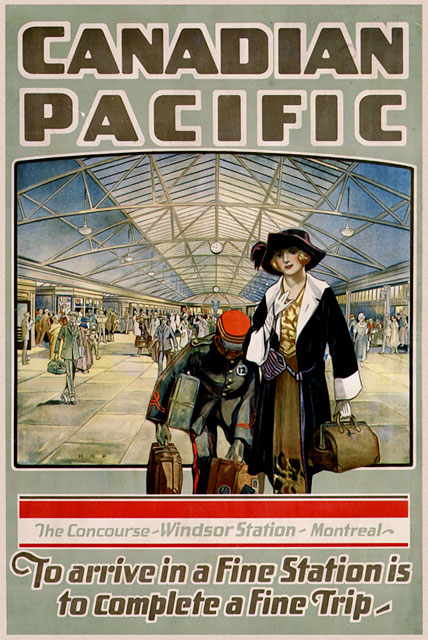

A group of British immigrants to Canada pose in front of the train arrival and departure board at CPR’s Windsor Station in Montreal in the 1920s. The company attracted settlers at central points in the British Isles and assisted in their placement on farms throughout Canada.

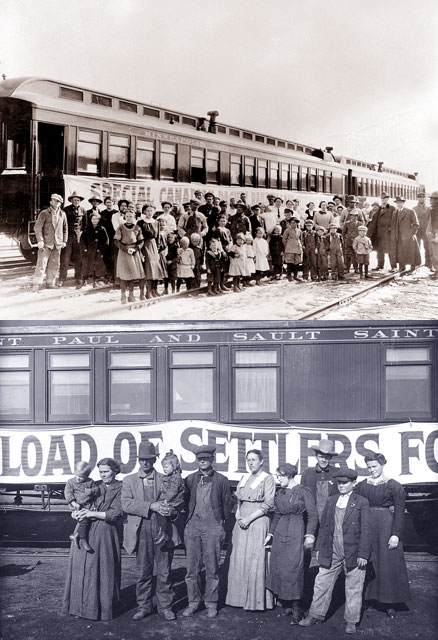

Bassano, AB, 1914. Ref: NS13230 (top) and A827 (bottom)

Top image: A party of colonists from Colorado arriving at Bassano, AB prepares to occupy their CP ready-made farms in the eastern section of the irrigation block in 1914. The CPR’s colonization efforts and achievements that went well beyond simply selling its lands remain unique among the land grant railways of North America.

Bottom image: Settlers standing in from of Minneapolis, Saint Paul and Sault Ste Marie Railway car.

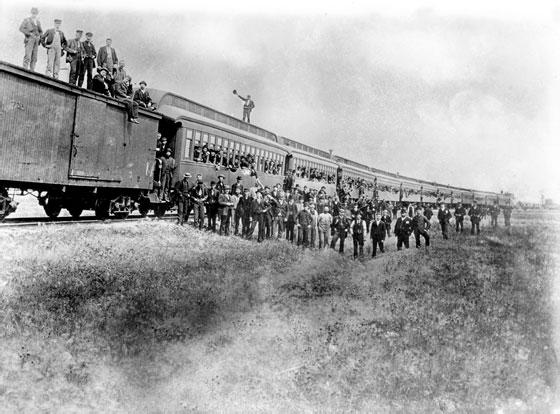

Canadian Prairies, 1890s. Ref: NS1159

Farm labourers in front of harvest excursion train.

The western farmer required seasonal workers to quickly harvest the wheat. CPR operated ‘harvest’ trains that brought able-bodied men to the farm to fill that niche. At their peak in the 1920s, these trains carried about 45,000 farm workers to help keep the economy growing.

1885-1890. Ref: NS12968

Although austere in appearance, the colonist sleeping cars, introduced by the CPR in 1884, were a decided improvement over the ordinary day coaches used for handling immigrant traffic to the Prairies during the preceding years. Available at no extra cost over the coach fare, the colonist cars provided upper and lower berth sleeping accommodation and a combination car heater and cook stove on which the occupants could prepare hot meals.

Unique among the land grant railways of North America, the CPR’s colonization efforts and achievements went well beyond simply selling its lands.

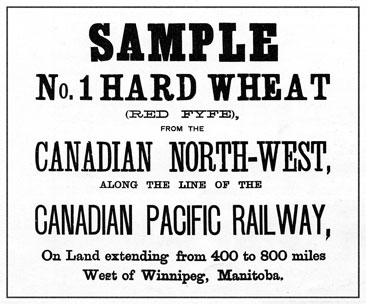

To help sell its land, the CPR set up 10 experimental Prairie farms along the railway tracks in 1884. An exhibit car full of crops grown on these farms toured around eastern Canada to show potential settlers from Ontario and Quebec the bounty of the Prairies.

In the 1920s and 30s the CPR experimental farms on the Prairies were instrumental in developing hardy new types of wheat that would thrive in the Northwest.

Both images from Strathmore, AB. Ref: GS25 (top), GS2 (bottom)

GS25 (top): Supply & Experimental farm, Strathmore, Alberta.

CPR experimental farms such as this one on the Prairies were instrumental during the ‘20s and ‘30s in developing hardy new types of wheat that would thrive in the Northwest.

GS2 (bottom): New settlers, western Canada.

Ref: NS12974

The CPR’s bilingual exhibition car crisscrossed Ontario and Quebec beginning in 1884 promoting the “great openings for immigrants to the boundless limits of the great Canadian North-West.” Varieties of grains and vegetables that could be grown on the Prairies together with specimens of ore, copper and iron from the Bow River were on display.

Indian Head, SK, 1900. Ref: A11171

Country grain elevators, similar to these at Indian Head, Saskatchewan, were introduced to the prairies in 1879, and soon became a symbol of Canada’s grain-producing areas in the West. The number of local elevators grew rapidly following the first great harvest in 1887, when the inadequacy of the fledgling grain storage and transportation system forced farmers to store their crops in two-bushel jute sacks on railway platforms, often in stacks which overshadowed the station building.

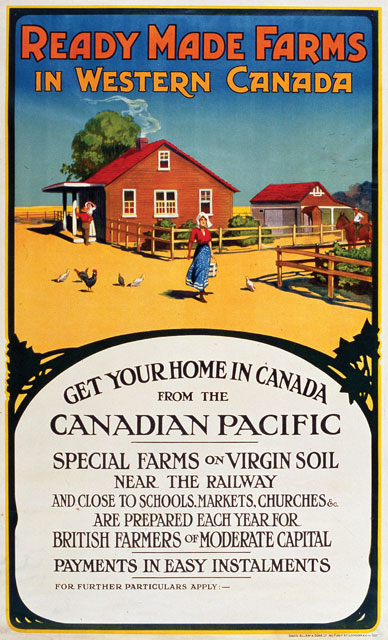

One unique challenge the CPR faced was that settlers did not know how to farm in the Canadian Prairie environment. In 1909, the CPR solved this problem by selling ready-made farms. Each farm came equipped with a house, barn, well and pump. The 65- to 130-hectare farms were fenced, with one third of the land plowed and ready to seed. They were located near schools, churches and, of course, the railway. The cost was ten equal annual payments of $1,300 for smaller farms and $2,500 for larger farms. The first ready-made farm colonies sprouted up in southern Alberta. Between 1909 and 1919, the CPR developed 762 ready-made farms in 24 colonies of five to 122 farms.

Ref: A12028

In the first part of the 20th century the CPR established a program consisting of ready-made farms to attract British settlers. Each quarter section and half-section farm came fenced with one third of the land plowed. The farms were located near schools, churches as well as the railway.

Between 1910 and 1920, the CPR invested heavily in irrigation initiatives in Southern Alberta, including construction of the Bassano Dam, Brooks Aqueduct, and roughly 4,000 kilometers of canals and ditches. Costing millions of dollars, these engineering works transformed 440,000 acres of semi-arid land into productive agricultural land. The project ranked as one of the largest irrigation systems on the continent.

Bassano, AB, circa 1915. Ref: A2081

In 1914, about a year before this photo was taken of the CPR’s Land Office at Bassano, Alberta, the company had completed an aggressive scheme to irrigate a large area of semi-arid land in southeastern Alberta. The plan included a 3.2 kilometer aqueduct constructed at Brooks, an enormous dam built at Bassano on the Bow River and about 4,000 kilometers of canals and ditches. Irrigation made southeastern Alberta “fairly fit for settlement.”

war efforts

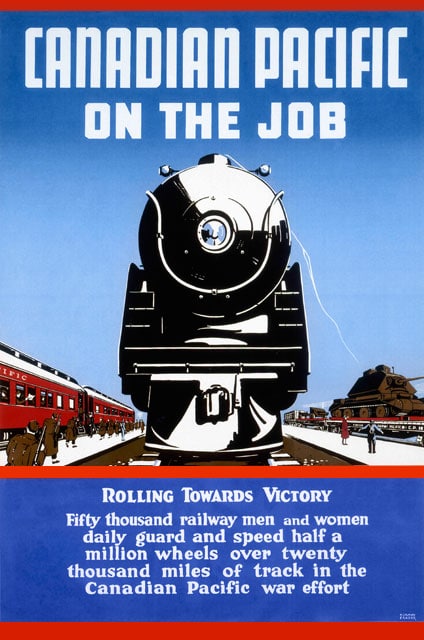

From the outset of war the CPR put the entire resources of the company at the British Empire’s disposal. This during the CPR’s heyday, when the railway was much more than just a railway. Not only were the railway’s trains and tracks at the British Empire’s disposal, but also its ships, shops, hotels, telegraphs, and, above all, its people.

Aiding the war effort meant transporting and billeting troops, building and supplying arms and munitions; arming, lending and selling ships.

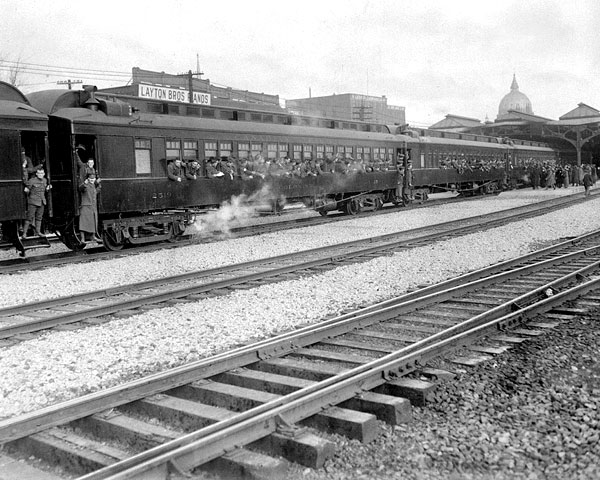

Montreal, QC, 1917. Ref: NS5477

The inaugural meeting of the Special Committee on War and National Defence, the predecessor of the Railway Association of Canada, was held in the CPR boardroom at Windsor Station in Montreal on October 23, 1917. Seated left to right: H.G. Kelley, President, Grand Trunk Railway; D.B. Hanna, Third Vice-President, Canadian Northern Railway, sitting in on behalf of the President, Sir William Mackenzie; Lord Shaughnessy, President, CPR; A.H. Smith, President, New York Central Railroad; E.W. Beatty, Vice-President and General Counsel, CPR; W.M. Neal, CPR, Secretary of the Committee.

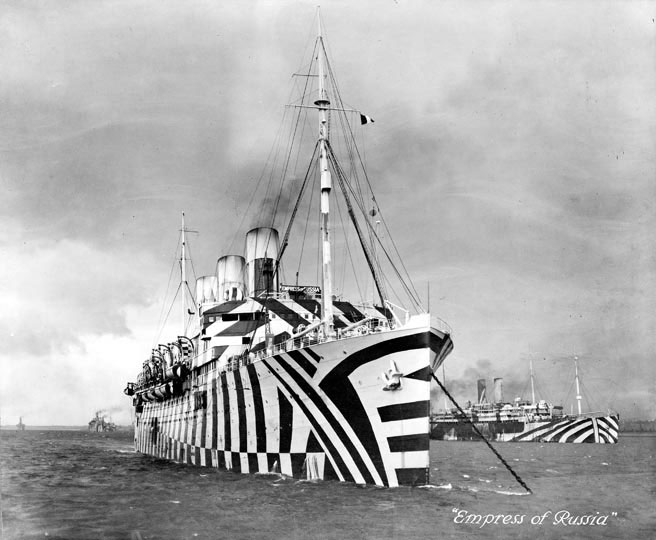

Fifty-two CPR ships were pressed into service during World War I, carrying more than a million troops and passengers and four million tons of cargo. Twenty-seven survived and returned to the CPR. Twelve sank, mostly torpedoed by U-boats; two sank by marine accident; and 10 were sold to the British Admiralty.

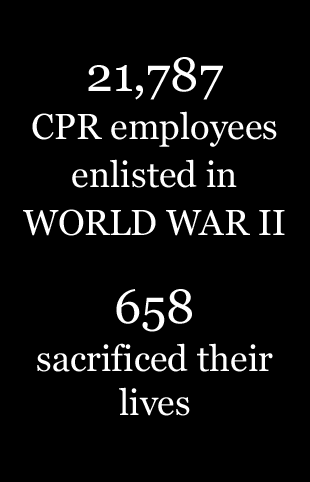

But the CPR’s most important contribution was its men and women, both at home and abroad. 11,340 CPR employees enlisted, a catastrophic 10 percent (1,116) were killed, and nearly 20 percent (2,105) were wounded. Two CPR employees received the coveted Victoria Cross and 385 others were decorated for valor and distinguished service.

The CPR also helped the war effort with money and jobs. The CPR made loans and guarantees to the Allies to the tune of $100 million. The CPR also took on 6,000 extra people, giving them jobs during the war, and when the fighting was over and the troops came home, the CPR found jobs for the ex-soldiers. 7,573 CPR enlistees came back to jobs with the company. And the CPR gave jobs to an additional 13,112 who made it back from overseas fighting

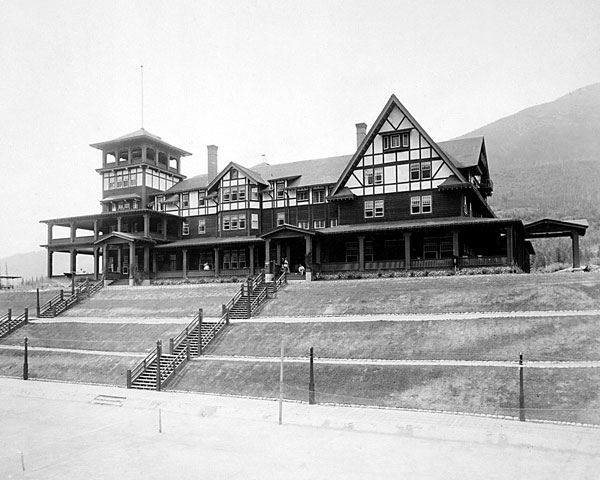

Balfour, BC, circa 1912. A8207

The Kootenay Lake Hotel at Balfour, BC, was built by the CPR in 1910 to provide first class lodgings for tourists and businessmen visiting the Kootenays. Closed to guests during WWI, the hotel was leased to the Dominion government in 1917 as a hospital for returned soldiers.

With the outbreak of World War II, the entire CPR network was again at the disposal of the Allied war effort. On land, the CPR moved 307 million tons of freight and 86 million passengers; including 150,000 soldiers, nearly 130,000 army and air force re-patriots, and thousands of sailors.

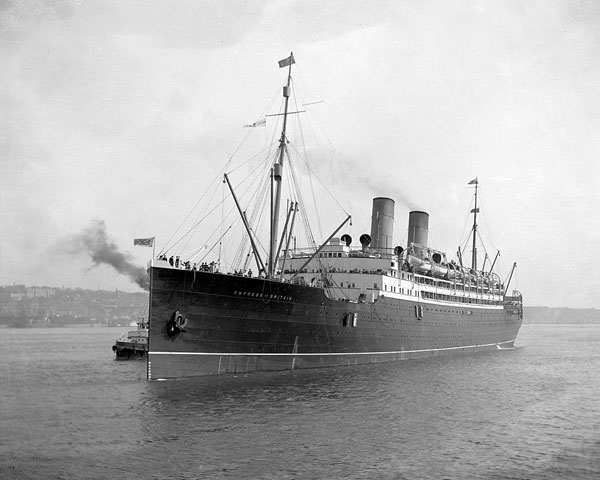

At sea, 22 CPR ships went to war with 12 of them being sunk, including the CPR’s largest passenger ship ever, which was almost as big as the Titanic — the Empress of Britain II.

In the air, the CPR pioneered the “Atlantic Bridge” – the transatlantic ferrying of bombers to Britain. The CPR set up pilot training schools and opened Canada’s strategic far north, creating Canadian Pacific Air Lines in 1942.

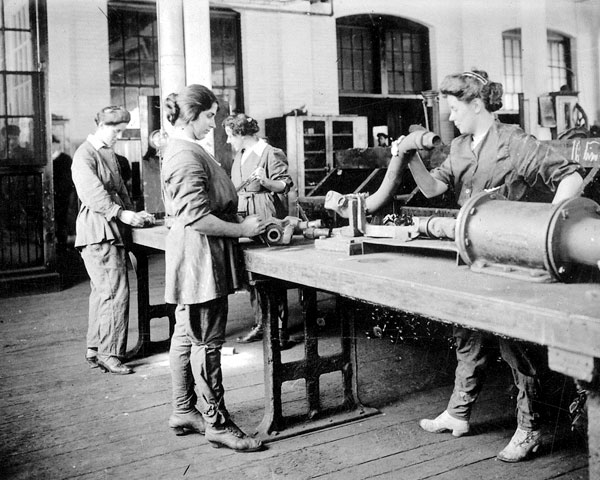

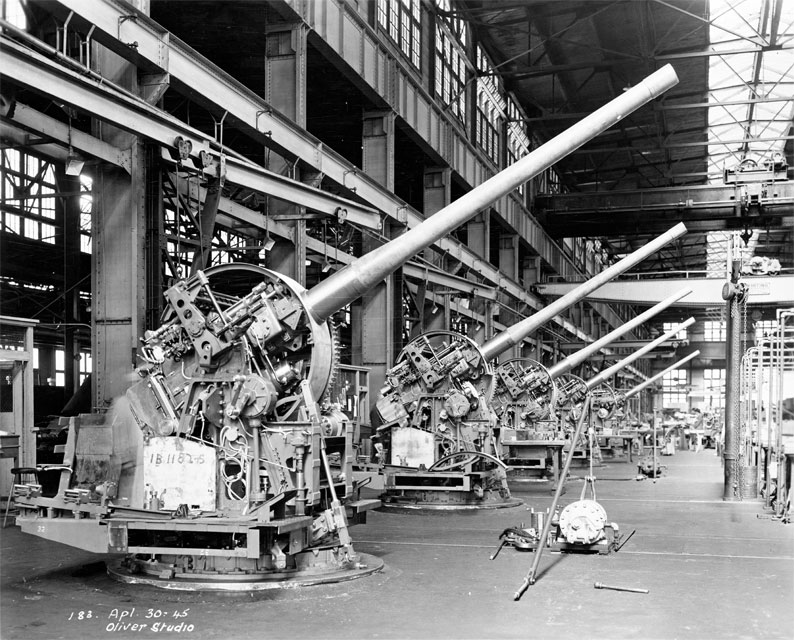

The CPR transformed major portions of its shops in Montreal and Calgary to build munitions, naval guns and tanks. By V-J Day, CPR shops had turned out 1,420 Valentine tanks; 75 main engines for corvettes, frigates and landing craft; over 600 naval vessel power equipment components; 3,000 naval guns and 1,650 naval gun mounts; 2,000 anti-submarine devices; and 120 range-finding and fire-control equipment.

Montreal, QC, circa 1942. Ref: NS3003

A machinist at work on one of the many parts for Valentine Tanks while co-worker in foreground repairs steam locomotive bells. World War II “Valentine” army tank production and locomotive repair went hand-in-hand at Canadian Pacific Railway’s Angus Shops in Montreal.

Sudbury, ON, 1943. Ref: NS4760

With the ranks of male employees thinned by enlistments in the armed forces during the Second World War, hundreds of women volunteered to take over a variety of jobs connected with the day-to-day running of a railway, particularly in the operating, mechanical, maintenance of way and communications departments. At the Sudbury engine terminal, CPR employees Myrtle Pearson and Julia Patrash took the traditional male task of wiping down locomotives between runs.

Wartime shop production signaled the end of the Great Depression and offered jobs to many laid-off CPR employees. And with the conscription debate raging on in Canada, the company also provided jobs on the home front to CPR employees’ offspring who wanted to contribute to the war effort.

The CPR also provided the memorable setting for the two Quebec Conferences it hosted at the Chateau Frontenac in 1943 and 1944. It was there, in 1943, that Churchill and Roosevelt set the stage for the D-Day invasion that turned the tides of World War II.

Quebec City, QC, 1943. Ref: WAR110

On two occasions during the Second World War, the Canadian Pacific Chateau Frontenac was appropriated by the Canadian Government to serve as the working headquarters for meetings between United States President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill of Great Britain to discuss Allied strategy. Among the important decisions arrived at during the first Quebec Conference in 1943 was the choosing of the Normandy area in France as the location of the invasion of German-occupied Europe in June the following year.

Quebec City, QC, 1944. Ref: WAR104

In 1943 and 1944, Quebec City’s Citadel and Chateau Frontenac distinguished themselves by hosting two War Conferences. With the towering Chateau Frontenac and mighty St. Lawrence River as backdrops, William Lyon Mackenzie King, Prime Minister of Canada, Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the United States, and Sir Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of Great Britain, surrounded by their chiefs of staff, sit for the media during the 1944 conference.

1941. Ref: WAR75-2

Members of one of the CPR’s Air Raid Precaution units stage a mobile display of their contribution to civil defence in the early 1940s. The A.R.P. was organized at the beginning of WWII for the purpose of protecting the travelling public and Company personnel and property in the event of bombing raids by enemy aircraft. Anticipating these attacks, fire-fighting, medical and other emergency equipment and supplies were placed at strategic locations throughout the system. Several thousand employees across the country received training in evacuating buildings, administering first aid, maintaining and repairing communications, electrical and sanitary services, and extinguishing incendiary bombs.

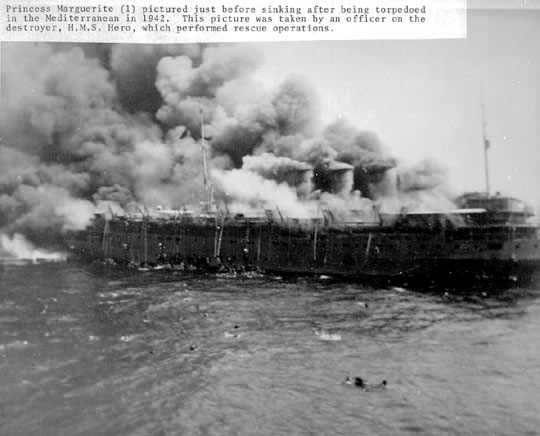

Mediterranean Sea, 1942. Ref: NS863

In August of 1942 the Princess Marguerite of the Canadian Pacific B.C. Coast Steamship Service sank in the Mediterranean, forty-nine minutes after being struck by a German torpedo while transporting troops from Port Said to Cyprus. Fourteen of the twenty-two Canadian Pacific vessels serving in the Second World War were lost through enemy action or related incidents, including the 42,000-ton passenger liner Empress of Britain, the Company’s flagship and largest civilian ship lost during the conflict.

Montreal, QC, circa 1940s. Ref: A17411

A group of Canadian soldiers gathered beneath the war memorial statue at the Canadian Pacific Windsor Station in Montreal, possibly awaiting departure for an unidentified “Eastern Atlantic Seaport” en-route to the war in Europe. Over 20,000 Company officers and employees, or one-quarter of the labor force, volunteered for active duty during the Second World War.

As the railway was being completed CPR management looked to grow its revenue as quickly as possible by adding additional services that leveraged off of the railway. Express (package delivery), telegraph, hotel, sleeping and dining car and other lines of business were added either as separate departments or companies.

Express and telegraph were profitable quickly without a huge outlay of capital. Other services such as sleeping and dining cars, as well as hotels, were kept in order to better control the quality of service provided. Small branch lines or competing railways were acquired to expand the CPR business area footprint, extending the reach of all of the railway’s services.

innovation & diversification

1897. Ref: A14054

The hustle and bustle of the Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo Railway’s (TH&B) Walnut Street freight office and shed in 1897. To gain access to the lucrative southern Ontario markets and a US gateway through Buffalo, the CPR bought a 27 percent interest in the TH&B in 1895 and then acquired the remaining shares in 1977 from Conrail.

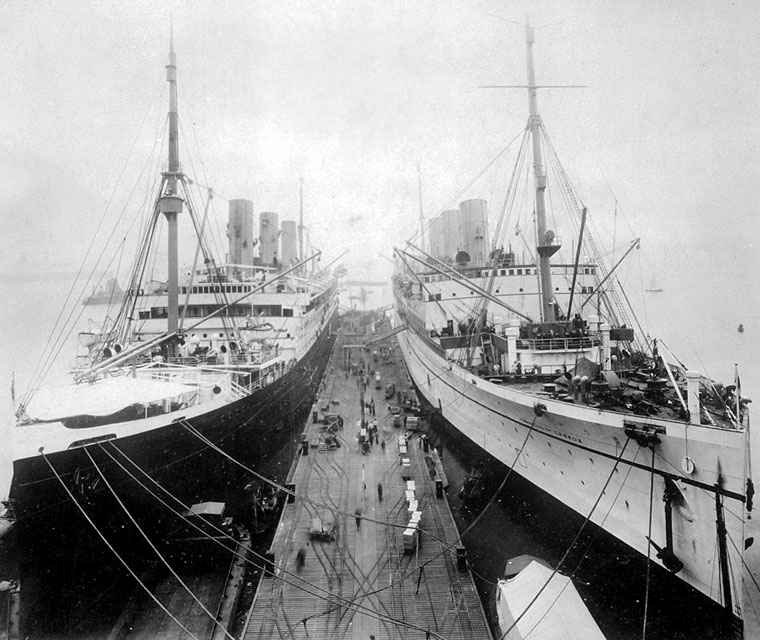

Steamships played an important part in the history of CPR from the very earliest days. Not only were ships used to bring materials to construction sites along rivers and lakes, they were also used to connect points along the railway as it was being built.

Trains ran from Toronto to Owen Sound, where passengers would then transfer to a CPR vessel, and arrive in Fort William (Thunder Bay) to continue on their journey by train. Even after the railway was built the CPR continued to profitably operate steamship and paddle wheel service on many rivers and lakes — they were complementary to the railway. Once the railway was completed, the CPR chartered and soon built their own passenger steamships as a link to the Orient.

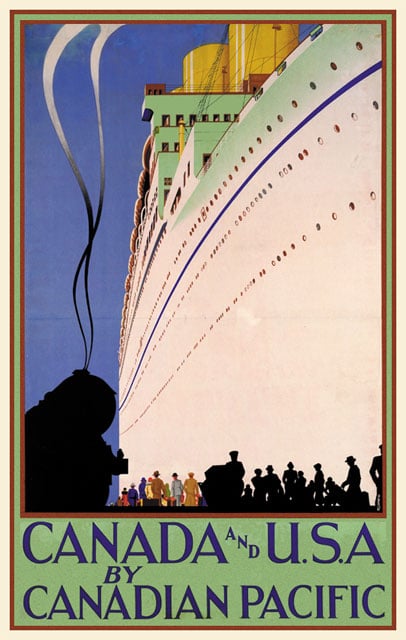

These sleek and modern steamships were christened with “Empress” names. In 1891, CPR adopted a new name for its steamship services — the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company. Travel to and from the Orient, along with cargo such as tea and silk, were an important source of revenue, aided by Royal Mail contracts. Atlantic passenger service started in 1903, it was now possible to travel from Britain to Hong Kong using only CPR ships, trains and hotels. Many immigrants made their “one way” trip from Europe to Canada on a CP ship.

From the late 1880s until after World War II, the company was Canada’s largest operator of Atlantic and Pacific steamships. With the introduction of long range passenger air service in the 1970s, CP retired the bulk of its passenger vessels.

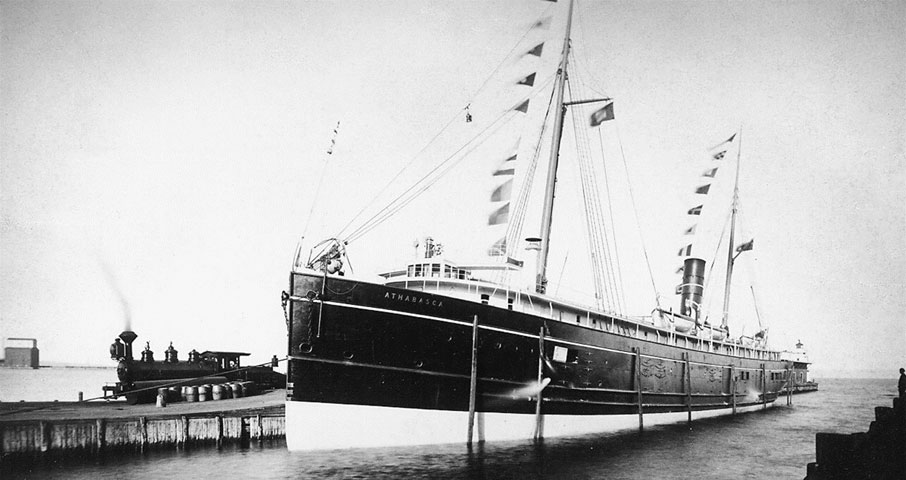

Port Arthur, ON, 1885-1890. Ref: A23631

The steamship Athabaska, pictured at Port Arthur, ON, and her two sister ships the Algoma and Alberta were built for Canadian Pacific in Scotland in 1883. The following year they inaugurated the Company’s Great Lakes service, carrying passengers and freight between Owen Sound and the Lakehead on a triweekly schedule. For the first two seasons much of the cargo space was taken up by railway construction material, pending the completion of the line north of Lake Superior linking the Company’s western rail system with the eastern provinces.

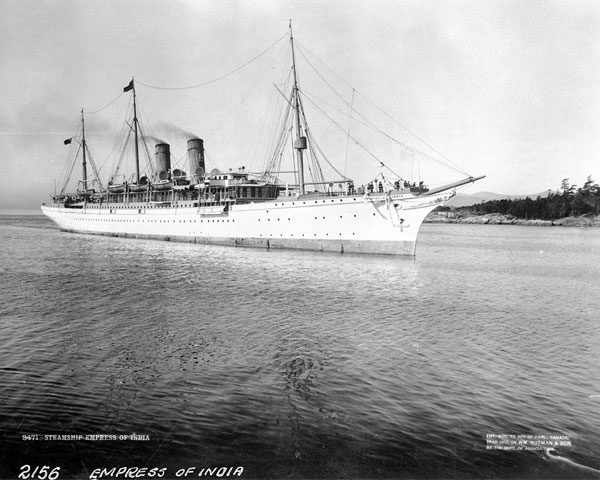

1891. Ref: NS2156

On the CP steamship Empress of India’s 1891 maiden voyage to Vancouver, BC she carried 131 passengers along with a precious cargo of tea and silk. The 5,905-ton Empress of India was the first deep sea vessel owned by CP. The event confirmed the Company’s, and Canada’s, position as a major participant in the growing trans-Pacific trade between North America and the Far East.

BC, 1914-1930. Ref: NS12126

Providing accommodation for up to 500 passengers, the B.C. Lake & River Service sternwheeler Sicamous was launched in 1914 from the Canadian Pacific shipyard at Okanagan Landing. The steamer was a familiar sight on Okanagan Lake for over 22 years before being laid up and later acquired by the community of Penticton, BC for a marine museum.

1931. Ref: NS22046

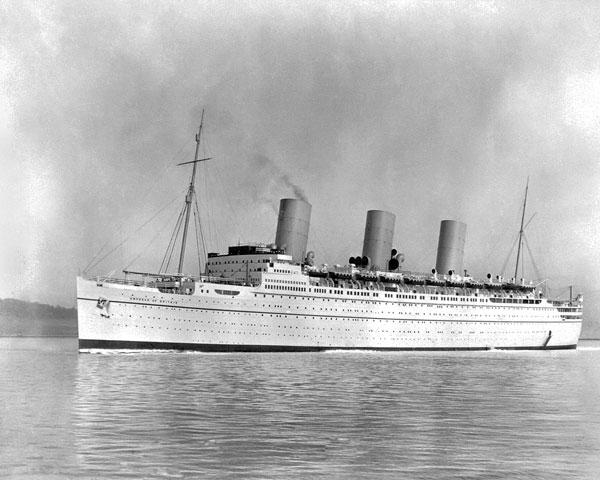

Flagship of the Canadian Pacific fleet following her entry into service in the summer of 1931, the 42,348-ton Empress of Britain was built at a cost of over $10 million to represent the Company’s bid to maintain its competitive position in the trans-Atlantic and winter cruise markets. The “Britain” could accommodate as many as 1,900 passengers and crew within her 760-foot length, making her the largest steamship to serve the North Atlantic route between Canada and Europe. In 1939 the ship was requisitioned by the British Government for wartime trooping service and while returning to Britain on her fifth voyage as a military transport was intercepted by enemy forces off the coast of Ireland and sunk on October 28, 1940.

With the diminishing role of ships as airlines took over transcontinental travel, CP Ships focused its operations to shipping goods as opposed to passengers.

CP Ships began container shipping in 1964, with ships able to carry 12 containers.

In 1984 CP co-founded the container shipping company Canada Maritime and acquired the company fully in 1993.

CP Ships’ growth strategy was to acquire small shipping lines and integrate them into a much larger entity. CP Ships was spun off as a separate entity from CP in 2001.

Ref: NS800

The first CP vessel designed for transporting containerized goods, the Beaveroak began service in 1965 between Europe and Canada. In 1970 the ship was lengthened, its container capacity tripled, and the name changed to CP Ambassador for use between England and Wolfe’s Cove container port near Quebec City.

Ref: NS2694

Launched in 1966, the 71,000 dwt Lord Mount Stephen was the first of a fleet of large-capacity ships built for Canadian Pacific (Bermuda) Limited a wholly-owned subsidiary formed by the Company in 1964 to own and operate ocean-going bulk carriers in the international trade. The new tanker was chartered to Shell Petroleum Company for handling crude petroleum from the Persian Gulf to Japan.

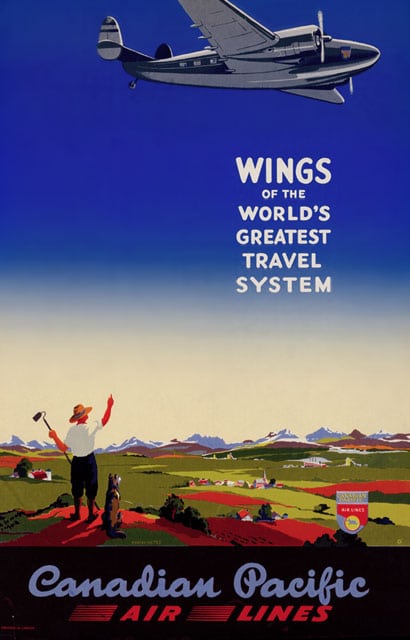

In the early 1940s, the CPR purchased ten bush airlines in a short time span, finishing with the purchase of Canadian Airways in 1942, to form Canadian Pacific Air Lines. Canadair C4 Argonauts, DC3s and then DC6s were the primary planes used in the first decade, and in 1958 the airline replaced many of these with Bristol Britannia turboprops.

The company entered the Jet Age in 1961 with the arrival of three Douglas DC8s, which became the fleet standard for the 1960s and early 1970s with DC8-40s and DC8-63s. In 1968, Canadian Pacific Air Lines was rebranded as CP Air.

The development of the polar route to the Far East from CP Air’s Vancouver base would become one of the cornerstones of the airline.

With large airplanes such as the Boeing 737 and 747s and experienced pilots, flights to Amsterdam, Australia, Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Shanghai were introduced, which helped the airline’s revenue grow from $3 million in 1942 to $61 million by 1964. Additional destinations served were Greece, Portugal, Peru, Argentina and Mexico.

CP Air was sold in 1987 to Calgary based Pacific Western Airlines. In April of that same year, PWA announced that the new name of the merged airline would be Canadian Airlines. In 2000, Canadian Airlines was taken over by and merged with Air Canada.

circa 1946. Ref: NS8686

Used as long-range maritime patrol aircraft during the Second World War, Canadian Pacific Airlines purchased four of these “Canso” flying boats from Crown Assets in 1945-1946 and employed them for several years between Vancouver and a number of communities along the coast of British Columbia. One of these aircraft had been credited with the sinking of a German submarine during the Battle of the Atlantic in 1944.

1955. Ref: NS26252

The Douglas DC-6 entered service with Canadian Pacific Airlines in 1953 on the trans-Pacific routes from Canada to Australia and Hong Kong. In addition to maintaining these services, this type of aircraft also inaugurated flights to Peru in the same year, Holland in 1955, and Portugal in 1957. The DC-6 was the last all-propeller-driven aircraft acquired by the airline, and was replaced on the Company’s international routes in 1958 by the turbo-prop Bristol “Britannia”, itself an interim type succeeded three years later by the pure-jet Douglas DC-8.

As part of the contract with the Government of Canada to build the transcontinentental railway, the CPR was granted 25 million acres of land, and these lands included petroleum and natural gas rights (mineral rights).

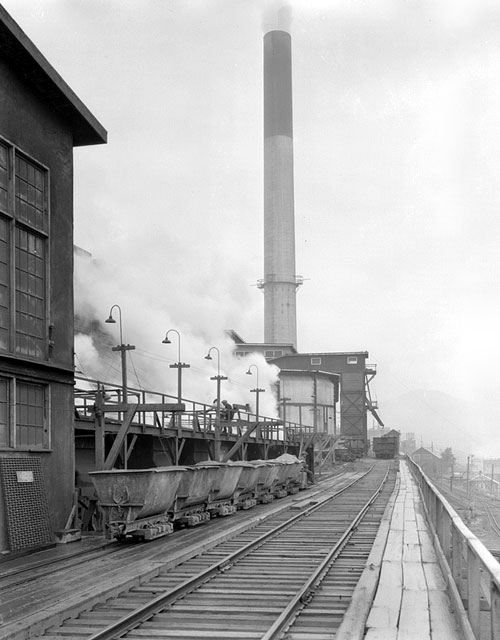

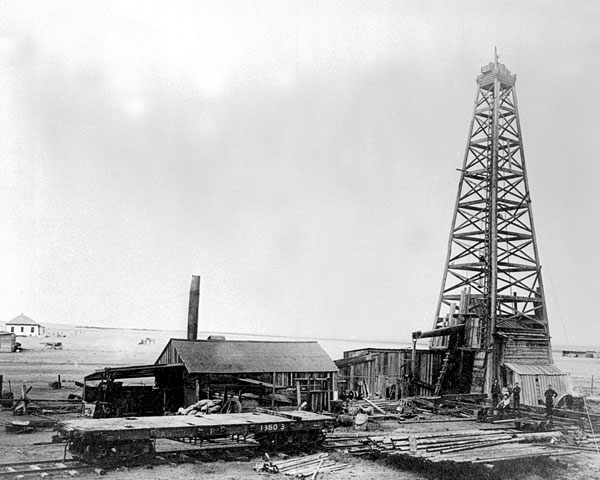

The CPR was the first company in Canada to discover and develop the use of natural gas as a source for heating fuel. In December 1883, while searching for water at Langevin AB, ~ 35 miles west of Medicine Hat, CPR employees discovered natural gas rushing out of the well tube. Unfortunately, two employees were injured in the following explosion and fire. Another well was drilled the following year, and the natural gas from this well was used to heat the station and an adjacent bunkhouse. This was the first recorded use of natural gas as a heating source in Canada.

In 1958 the CPR created a subsidiary – Canadian Pacific Oil and Gas (CPOG), and passed all of the mineral title lands to the subsidiary. An aggressive exploration and production program was initiated on company owned lands.

In 1971 CPOG merged with Central-Del Rio Oils to become PanCanadian Petroleum. One of the first projects the new company embarked on was the development of shallow gas in southern Alberta. PanCanadian’s holdings increased over the next twenty years making it the largest independent producer of crude oil and natural gas in Canada.

In 2001 PanCanadian was spun off from the CPR, and in 2002 merged with Alberta Energy Company to form Encana, one of North America’s largest independent energy companies.

near Medicine Hat, AB. Ref: A37360

In December 1883, a CPR construction crew drilling for water for the company’s steam locomotives, accidentally discovered natural gas at the Langevin siding about 35 km west of Medicine Hat, AB, marking the beginning of Western Canada’s petroleum industry. CP created a Department of Natural Resources in 1912 to administer the company’s land grants and their natural resources including timber, oil, gas and mineral rights.

AB. Ref: NS21911

In December 1883, while searching for water at Langevin AB , CPR employees discovered natural gas rushing out of the well tube. The railway became the first in Canada to discover and develop the use of natural gas as a source for heating fuel. The CPR formed its Department of Natural Resources in 1912, incorporated Canadian Pacific Oil and Gas in 1958 which became PanCanadian Petrolem in 1971.

Mining and railroading go hand in hand since railroads are usually required to move heavy ores from remote mines.

The CPR initially got into the mining business — not because it wanted to, but because it had to. The owner of the original smelter at Trail, BC, also owned railway lines in the area that the CPR desperately wanted to control. The smelter owner, Fredrick Augustus Heinze, wanted to sell all of his interests in the area, and was not willing to sell the smelter or other assets he owned in the area seperately from the railway — it was “all or nothing.” The CPR bought out Heinze in 1898, and for the next 88 years was a major player in the Canadian mining industry.

Ref: NS21911

In December 1883, while searching for water at Langevin AB , CPR employees discovered natural gas rushing out of the well tube. The railway became the first in Canada to discover and develop the use of natural gas as a source for heating fuel. CP formed its Department of Natural Resources in 1912, incorporated Canadian Pacific Oil and Gas in 1958 which became PanCanadian Petroleum Ltd. in 1971.

Within two years of taking over Heinze’s disparate assets, the CPR had doubled the capacity of the smelter and merged its smelter with local mines to form one company with one management team, the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company of Canada (renamed Cominco in 1966). In 1913 it acquired the rich Sullivan Mine in nearby Kimberley, BC, which did not close until 2001 after 92 years of production.

Cominco expanded in the following decades, acquiring mines/mining interests not only in Canada but in the U.S., Spain, Australia and elsewhere. Cominco was sold to other interests in 1986, and today is owned by Teck Resources, based in Vancouver.

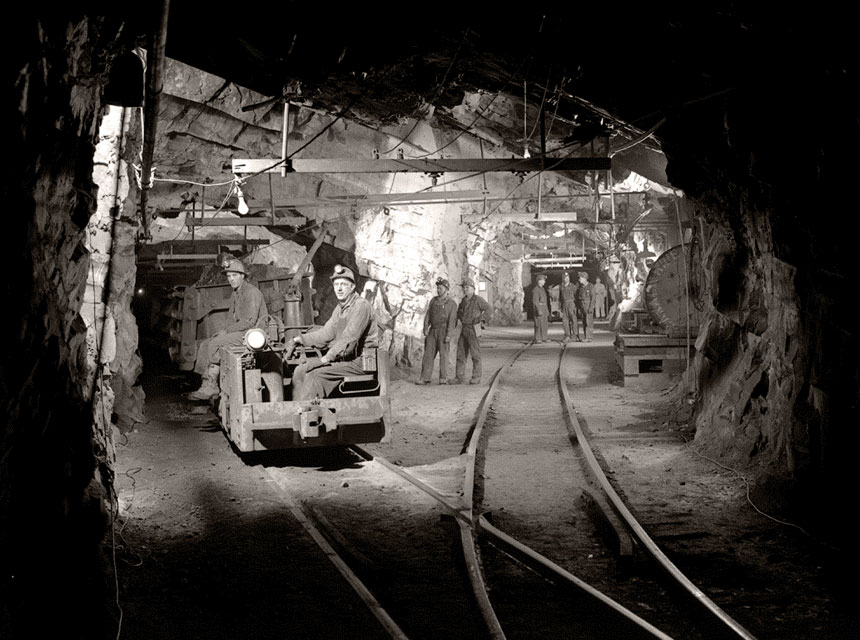

near Rossland, BC. Ref: NS16902

The Centre Star Mine was discovered in 1890 near Rossland, BC and was one of the original claims which led to the birth of the metallurgical industry in the West Kootenay area during the mid-1890s. The CPR purchased many of these properties in 1898 and formed what later became the Consolidated Mining & Smelting Company. Renamed Cominco Limited in 1966, the company was sold to other interests in 1986.

One of the key costs in mining is separating the ore from the rock, and Cominco management recognized that to remain profitable after the commodity boom of the first World War they would need to lower costs for processing the ore from the Sullivan mine.

Cominco hired Randolphe ‘Ralph’ William Diamond, a prominent metallurgist from Ontario, to head up the company’s milling operations and to conduct testing on the Sullivan ore, to come up with the best solution to separate the valuable ore from the rock.

Diamond led a five-man research team that developed a new process for ore separation known as “differential froth flotation,” and this process would have a major impact on the entire industry. Differential flotation allowed minerals to ‘float’ by sticking to bubbles formed in certain mixtures of chemicals and oils. The bubbles formed a surface froth, which could then be skimmed off, separating the mineral from the rest of the mixture. This process was a major step forward for the company, and it unlocked the treasures of the Sullivan’s zinc-lead-iron sulphide ore.

By 1923, Cominco had built the first successful large-scale differential flotation operation anywhere and this success catapulted Cominco Ltd. into the forefront of Canadian mining companies.

The original charter of the CPR granted in 1881 provided for the right to create a telegraph and telephone service.

The telephone had barely been invented, but telegraph was well established as a means of communicating quickly across great distances. Being allowed to sell this service meant the railway could offset the costs of constructing and maintaining poles and telegraph lines — which the CPR needed for its own purposes for dispatching trains.

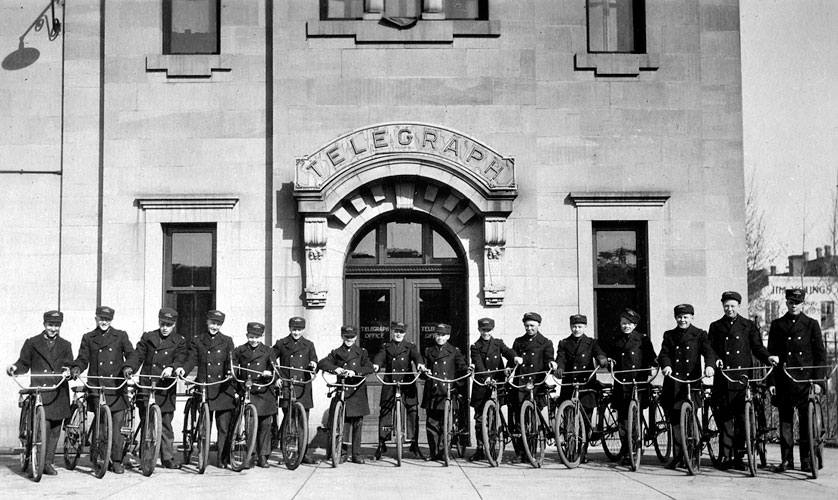

In 1882 a separate Telegraph Department was set up within the CPR, which was responsible for the building and maintenance of the telegraph network as well as its commercialization. In 1886 a telegraph message was sent for the first time from the Atlantic to the Pacific by an all-Canadian route.

Paid for by the word, the telegram was an expensive way to send messages, but they were vital to businesses. An individual receiving a personal telegram was seen as being someone important. Messengers on bicycles delivered telegrams and picked up a reply in cities. In smaller locations the local railway station agent would handle this on a commission basis. To speed things, at the local end where telephone service was established, messages would first be telephoned.

Today when we think of package delivery — or express — companies like FedEx come to mind, but until the mid-20th century the parcel delivery business was a virtual monopoly of the railway companies.

The Dominion Express Company was formed in 1873, and in 1884 was taken over by the CPR. As tracks were completed and branch lines extended, so was the reach of the express service. It was renamed the Canadian Pacific Express Company in 1926.

It operated as a separate company, with the railway charging it to haul express cars on trains. All sorts of small shipments could be found on express rail cars: business packages, personal items for relatives and goods purchased by catalogue. Refrigerated cars carried cream, butter poultry, eggs, fish and seafood. There were even special express cars for automobiles, horses, and prized livestock for exhibitions.

Money orders were a large business for the CPR. In an era before credit cards and the Internet, money orders were a safe means of transporting funds to distant places rather than incur the risk of mailing cash.

People often headed for the nearest railway station when they needed to send money and the hours were far more convenient than banks which, in that era, were only open on weekdays and closed at 3 PM. Gold, silver, cash and jewellry were often carried on express cars with armed guards.

At its height, the Canadian Pacific Express subsidiary maintained more than 8,900 agencies in Canada and around the world.

The railway express business began to decline in the 1960s due to trucking and the decline of passenger trains, along with the express cars that were part of the train.

Liverpool, UK. Ref: NS9016

Dominion Express Company motor trucks delivering goods to the Liverpool docks for shipment aboard a Minnedosa-class vessel of CP’s Atlantic fleet. The express company, a wholly-owned but separately operated and managed subsidiary of CP, maintained more than 8,900 agencies throughout the world.

near Hope, BC. Ref: NS7865

The Quintette Tunnels on the former Kettle Valley Railway.

The difficulties often encountered in building a railway through mountainous terrain are illustrated by the Kettle Valley Railway’s efforts to overcome the Coquihalla River in southern British Columbia. Within a distance of less than 1,800 feet, four tunnels and two bridges were required to cross the Coquihalla Canyon between Othello and Hope. This location is now a part of the Coquihalla Canyon Recreation Area, and accessible to the public as a hiking trail.

BR223

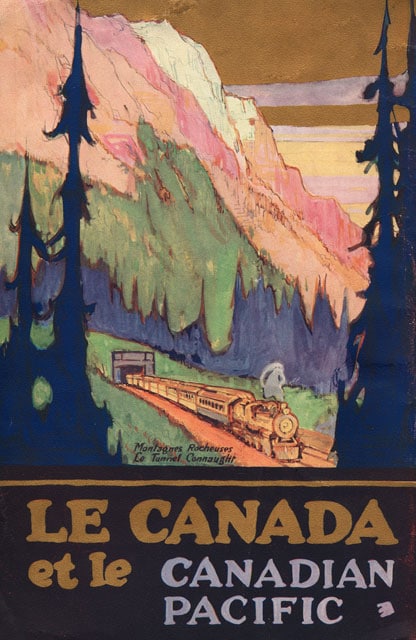

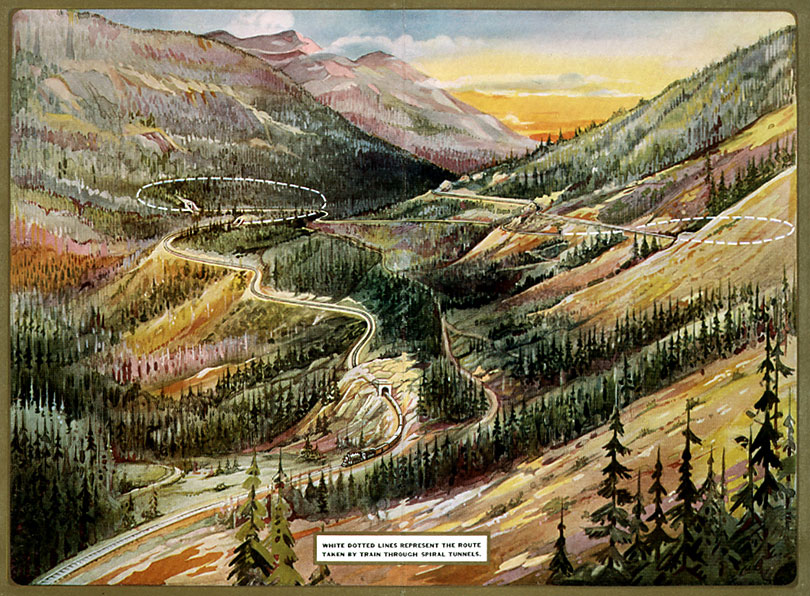

The Spiral Tunnels, located 50 miles west of Banff, consist of two grade-reducing spirals that cross over themselves. Opened for traffic on September 1, 1909, the Spiral Tunnels were built to replace a steep section of track called “The Big Hill”, with its 4.5% grade.

As an example of how it works, an eastbound train leaving Field (at the bottom of the illustration) would travel across the Kicking Horse River and into the Lower Spiral Tunnel. It spirals to the left up inside the mountain for 891 metres and emerges 15 metres (50 feet) higher. The train then crosses back over the Kicking Horse River and into the 991 metre tunnel in the mountain on the right of the illustration. The train completes another loop, emerging 17 metres (56 feet) higher and continues to the top of Kicking Horse Pass.

near Rogers Pass, BC, 1984. E5715-22

Mount Macdonald Tunnel

In 1982 CPR started construction on a project to make it possible for longer and heavier trains to travel through Rogers Pass with ease. The project, which consisted of a 1,229-metre long viaduct, a shorter 1.9-kilometre tunnel, and a longer 14.7-kilometre tunnel, was completed in the late 1980s.

This modern-day engineering feat is the longest tunnel in the western hemisphere.

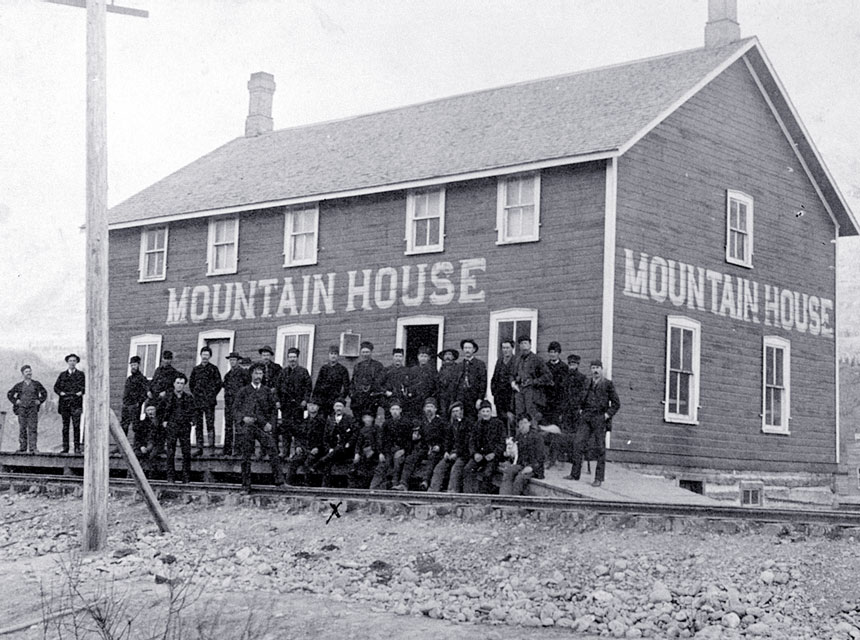

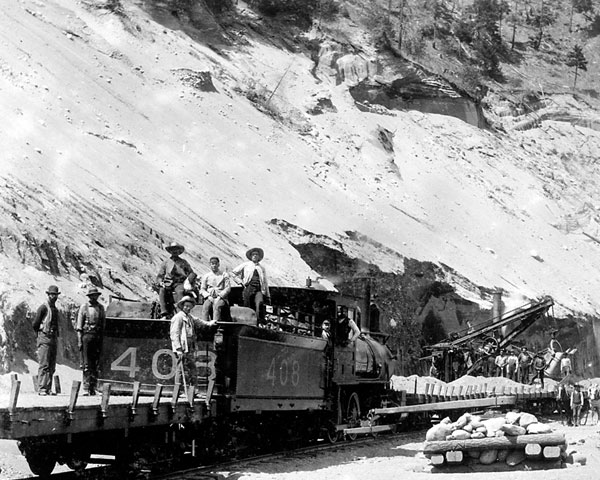

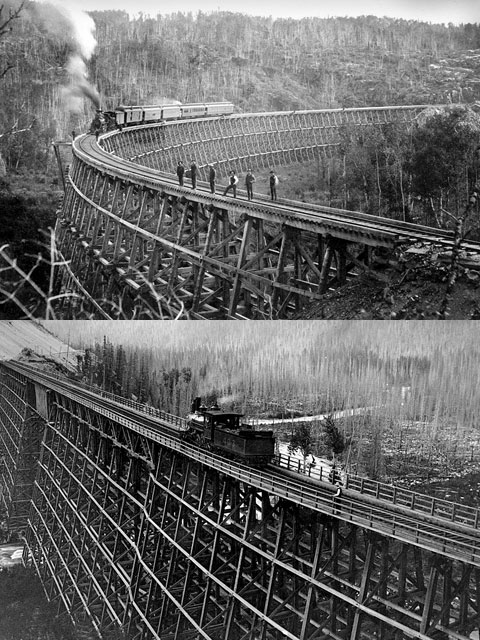

Top: circa 1886. Ref: A8022 Bottom: circa 1888. Ref: NS25985

Top image (A8022).

CPR passenger train on the Horseshoe trestle.

Bottom image (NS25985).

In the spring of 1885, construction began on the largest structure to date, the CPR’s Mountain Creek Bridge. Built with more than two million board feet of lumber, the bridge was 50 meters (164 feet) high and spanned a distance of 331 meters (1,068 feet). Perched on the bridge is locomotive No. 403, a Brown class S.D. 2-8-0 built at the Canadian Pacific New Shops in Montreal in December 1886. It was assigned to transcontinental passenger service between Donald and Revelstoke BC in the late 1800s.

As Canadian Pacific grew and diversified, Canadian Pacific Railway began to focus again on its core business under the guidance of its chairman and C.E.O. William Stinson, a fourth-generation CPR railroader.

To capitalize on its refocusing efforts CPR expanded its rail network in 1990, taking full control of the Soo Line in the U.S. Midwest – a company it had a majority interest in since the 1890s. The Soo Line had already absorbed the Milwaukee Road in 1985. Three years before, in 1982, the Soo Line bought the Minneapolis, Northfield and Southern (MNS). In 1991, CPR bought the bankrupt Delaware and Hudson Railway (D&H) giving it access to ports in the U.S. Northeast.

With the goal of unlocking shareholder value, Canadian Pacific spun out its five subsidiaries into separate companies on October 3, 2001. Today, Canadian Pacific Railway is a fully independent, public company with shares trading on the major stock exchanges in Toronto and New York.

CPR’s 12,400-mile network extends from the Port of Vancouver in the Canada’s West to The Port of Montreal in Canada’s East, and to the U.S. industrial centers of Chicago, Newark, Philadelphia, Washington, New York City and Buffalo.